I can’t remember now if the tip came in first to Howie Kurtz or to me when we were both reporters at The Washington Post. But one of us heard that members of the Reagan Administration were taking part in a nifty little boondoggle that Charles Z. Wick had approved at the United States Information Agency. Here was the scam. If a high-ranking government employee was willing to drop by the U.S. Embassy when he and his family jetted off to London, Paris, or some other exotic city on vacation, the government would pick up the cost of his airfare. All he had to do was give an hour long “briefing” to embassy employees to qualify for the taxpayer paid ticket.

Wick was furious when we confronted him and during our exchange he blurted out that Reagan staffers were not the only Washingtonians who were getting free airfare courtesy of Uncle Sam.

Journalists were too.

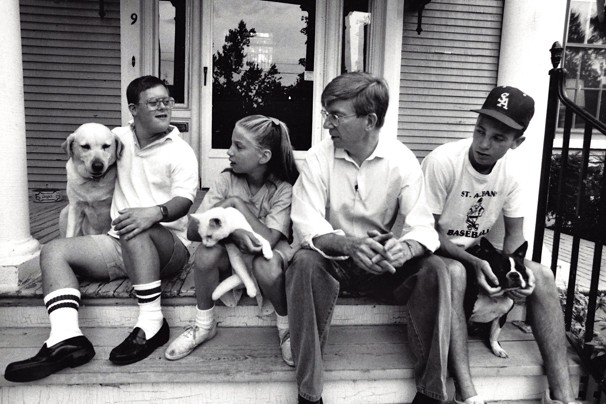

Kurtz and I quickly obtained a list of media stars who had become USIA frequent flyers. One of them was George F. Will. The job of confronting Will fell on me and he happened to be on vacation with his family at the beach when I tracked him down. His answer made it crystal clear to me that I was a nobody when compared to him and I certainly had no right to question him about his ethics.

I ended up writing a story about Will and the others on the USIA travel list, but my investigative expose got spiked by managing editor Howard Simons . I was never told exactly why, but later I heard a rumor that Will had telephoned the Post hierarchy and complained. Will was the most popular columnist in the writers syndicate that the Post sold to other newspapers.

The release of my story would have embarrassed Will, in part, because he had come under fire in the media earlier for blurring the line between journalism and partisan politics. He’d been criticized for helping Ronald Reagan prepare for the 1980 presidential debates with Jimmy Carter. That little episode was part of a bigger scandal dubbed “debategate” that involved charges that someone had given Reagan briefing papers before the debate that had been stolen from the Carter campaign. Will was one of the suspects.

Based on my only conversation with Will, I came away thinking he was arrogant. I didn’t think much of him as a journalist or a person, for that matter. But since then, my opinion of him has softened — not because of his politics — but because of the character that he has shown as a father.

Will has written previously about his son, Jonathan Frederick Will, who has Down Syndrome. But a column published this week in the Post on the occasion of Jonathan’s 40th birthday was a truly moving and insightful piece about parent/child relationships when an mental disorder is involved.

Perhaps this column says more about Will’s character than the brief dressing down that he gave me more than twenty years ago.

By George F. Will, Published: May 2

The Washington Post

When Jonathan Frederick Will was born 40 years ago — on May 4, 1972, his father’s 31st birthday — the life expectancy for people with Down syndrome was about 20 years. That is understandable.

The day after Jon was born, a doctor told Jon’s parents that the first question for them was whether they intended to take Jon home from the hospital. Nonplussed, they said they thought that is what parents do with newborns. Not doing so was, however, still considered an acceptable choice for parents who might prefer to institutionalize or put up for adoption children thought to have necessarily bleak futures. Whether warehoused or just allowed to languish from lack of stimulation and attention, people with Down syndrome, not given early and continuing interventions, were generally thought to be incapable of living well, and hence usually did not live as long as they could have.

Down syndrome is a congenital condition resulting from a chromosomal defect — an extra 21st chromosome. It causes varying degrees of mental retardation and some physical abnormalities, including small stature, a single crease across the center of the palms, flatness of the back of the head, a configuration of the tongue that impedes articulation, and a slight upward slant of the eyes. In 1972, people with Down syndrome were still commonly called Mongoloids.

Now they are called American citizens, about 400,000 of them, and their life expectancy is 60. Much has improved. There has, however, been moral regression as well.

Jon was born just 19 years after James Watson and Francis Crick published their discoveries concerning the structure of DNA, discoveries that would enhance understanding of the structure of Jon, whose every cell is imprinted with Down syndrome. Jon was born just as prenatal genetic testing, which can detect Down syndrome, was becoming common. And Jon was born eight months before Roe v. Wade inaugurated this era of the casual destruction of pre-born babies.

This era has coincided, not just coincidentally, with the full, garish flowering of the baby boomers’ vast sense of entitlement, which encompasses an entitlement to exemption from nature’s mishaps, and to a perfect baby. So today science enables what the ethos ratifies, the choice of killing children with Down syndrome before birth. That is what happens to 90 percent of those whose parents receive a Down syndrome diagnosis through prenatal testing.

Which is unfortunate, and not just for them. Judging by Jon, the world would be improved by more people with Down syndrome, who are quite nice, as humans go. It is said we are all born brave, trusting and greedy, and remain greedy. People with Down syndrome must remain brave in order to navigate society’s complexities. They have no choice but to be trusting because, with limited understanding, and limited abilities to communicate misunderstanding, they, like Blanche DuBois in “A Streetcar Named Desire,” always depend on the kindness of strangers. Judging by Jon’s experience, they almost always receive it.

Two things that have enhanced Jon’s life are the Washington subway system, which opened in 1976, and the Washington Nationals baseball team, which arrived in 2005. He navigates the subway expertly, riding it to the Nationals ballpark, where he enters the clubhouse a few hours before game time and does a chore or two. The players, who have climbed to the pinnacle of a steep athletic pyramid, know that although hard work got them there, they have extraordinary aptitudes because they are winners of life’s lottery. Major leaguers, all of whom understand what it is to be gifted, have been uniformly and extraordinarily welcoming to Jon, who is not.

Except he is, in a way. He has the gift of serenity, in this sense:

The eldest of four siblings, he has seen two brothers and a sister surpass him in size, and acquire cars and college educations. He, however, with an underdeveloped entitlement mentality, has been equable about life’s sometimes careless allocation of equity. Perhaps this is partly because, given the nature of Down syndrome, neither he nor his parents have any tormenting sense of what might have been. Down syndrome did not alter the trajectory of his life; Jon was Jon from conception on.

This year Jon will spend his birthday where every year he spends 81 spring, summer and autumn days and evenings, at Nationals Park, in his seat behind the home team’s dugout. The Phillies will be in town, and Jon will be wishing them ruination, just another man, beer in hand, among equals in the republic of baseball.

I saw that column and liked it as well. The news about Arthur Miller’s “unclaimed” son that surfaced after Miller’s death had the reverse effect on me. It undermined many of the messages that his plays conveyed. A recent memoir by Styron’s daughter touched on this issue briefly and she seemed to think that sending your Down’s Syndrome baby post-haste to an institution was common in 1966. Well, there was no questions of this with my cousin in 1967, so I don’t think it was a given.

(BTW, evidently Styron also liked to tell her “funny” stories about the residents of a nearby instiutions for the mentally disabled; these depicted them as “crazy murderers” who might be out to get you. My opinion of Styron has similarly plummeted to Grand Canyon levels.)

I guess that tells you that can or agree with many people’s public convictions (Dickens comes to mind, as well), but find the actions they take in life less than honorable. And, that can work in reverse too as in this story.

I saw this article awhile back and was deeply moved. My husband and I recently adopted our 4th son from the Ukraine who has Down Syndrome. Our son, Dima, was locked away in an orphanage and about to be transferred to an adult mental institution to live out the rest of his years. By the grace of God we got to him in time and Dima has now been a part of our family for almost 1 year. What my husband and I saw while we were over there shook us to the core and we have vowed to our son that we would help many more like him find families of their own. Our son is a happy, relatively healthy, joyful, silly, and challenging little boy. My biological children relish each moment they have with him and they will all tell you that adopting a child with special needs was one of the best decisions we made as a family.