One of the last times I returned to Fowler, Colorado, was when I was working for The Washington Post and my good friend and editor, Walt Harrington, urged me to revisit my teenage home and write about my sister’s death. Alice died in a car accident and is buried there.

Even though my parents moved away from Fowler in 1970, they wanted their ashes taken there for internment — so after my mom died in 2013 and my father passed away earlier this year, it fell upon my brother, George, and me to carry out their wishes.

Not a day goes by when I don’t think of my parents and I am glad they were wise enough to have us make the journey together. In the eyes of my parents, it was a “reunion” and a time to remember when the five of us had lived together as a family. For me, it was time to grieve, to bond with my brother, to honor our parents and to ponder many of the same questions about death that had haunted me nearly thirty years ago when I set out on a trip to understand my sister’s death.

MISSING ALICE: The Story of My Sister, Her Death, and My Search for Answers

(First published in the Washington Post in 1986)

Midway across Ohio, the man beside me on the DC-10 asked where I was going.

“Fowler, Colorado. A little town of about a thousand people near Pueblo.”

“Why would anyone go to Foouuller?” he asked, grinning as he exaggerated the name.

“A death. My sister.”

“Sorry,” he mumbled and turned away.

I was relieved. I didn’t have to explain that my sister had been dead 19 years. Alice was killed when I was 14. She was two years older and we had been inseparable as children.

I couldn’t talk about her death at first. My voice would deepen, my eyes would fill with tears. My parents would cry at the mention of her name, and we rarely spoke of her. Then it seemed too late.

After I left home, my mother would phone me each February 13 and remind me that it was my sister’s birthday. Year after year, I would forget — and find myself angry with my mother’s insistent reminders. It was just before last Christmas, as I shuffled boxes in the basement, that I ran across Alice’s picture and clipping describing her death.

“A tragic accident Tuesday, June 14, about 7:05 p.m., took the life of Alice Lee Earley…” I sat down on the concrete floor, closed my eyes and tried to picture her. I couldn’t. I tried to focus more sharply. Alice eating Sugar Pops beside me at the breakfast table. Alice washing the green Ford Falcon. Alice stepping on my toes while singing in Church.

The events I recalled vividly. Alice’s face I recalled not at all.

I could only see the girl in the photograph — an image I had never liked, the face being without joy or expression. But in my mind I found no other. For the next week, I seemed to think of Alice constantly.

One night I awoke in bed, turned to my wife, and said, “Alice, are you there?” It took me an instant to realize what I had done.

When I called my parents, now living in South Dakota, and told them I was returning to Fowler, my mother said, “Good, everyone always acts like Alice never existed.”

I was at church camp when Alice died. The camp director shook me awake in the middle of the night and said my father was in his office. I padded barefoot on the barrack’s cool concrete floor toward a yellow sliver of light escaping from beneath a closed door. Inside, my father was crying. I had never seen him cry. I liked camp and I hated to leave, but I rode home quietly in the front seat between my parents.

My mother sobbed.

My father was silent, though once he smacked his palm fiercely atop the steering wheel.

I tried to remember the last thing I had said to Alice, but I couldn’t. So I thought of the girl I had met at camp the day before, about how I had hoped to sit next to her at evening vespers tomorrow, about how my friend, Eddie, would take my place. I knew the camp director would announce at breakfast that my sister was dead; Everyone would feel sorry for me. Maybe the girl would write me a letter.

On the way home we stopped at the house of the woman driving the car that had struck Alice. Flora Ledbetter came out of the bedroom in a white terry cloth robe, her eyes red. She sobbed. My father, a Disciples of Christ minister, said she was not to blame. Mr. Ledbetter put his arm around my shoulder. My mother hugged Mrs. Ledbetter. I felt sorry for her.

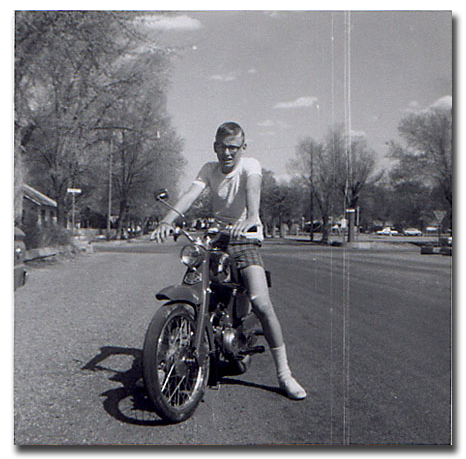

People came to the parsonage all that day. With each new wave, my parents repeated how Alice had died. “This is part of some greater plan,” one woman offered. I escaped to the garage, where I found my Honda 50 — its front wheel bent, its spokes snapped, its battery case cracked. Alice’s blood dotted the gas tank. I loved that scooter.

On summer mornings, I would slice through the steam above the warming country blacktop, my shirt unbuttoned and whipping my back. The Mexicans picking cucumbers, cantaloupes and watermelons in the fields would pause and lance as I passed at full throttle, 45 miles per hour. When my father found me in the garage, I’d cleaned off everything but the blood and was trying to straighten the mangled wheel with a hammer.

“I think I can fix it,” I said.

The next day it was gone.

Fowler is nine miles west of Manzanola, 18 miles west of Rocky Ford and 28 miles west of La Junta. No planes, no trains, no bus stations. The Arkansas River keeps the flat, rocky land around Fowler, population 1,243, rich for watermelons, sugar beets, sweet corn and cantaloupes. Fowler is nine blocks square. I think of it as home.

My family had moved six times by my fourteenth birthday, the year we arrived in Fowler. The constant migration made Alice and me close, as did the nearness in our ages. Our brother, George, was six years older than I. Alice was alive for only the first year we lived in Fowler, and most of my memories of the town do not include her.

But walking the streets of Fowler again helped me remember: Alice working behind the soda fountain at Fowler Drug, mixing me 15-cent cherry Cokes, Alice walking to the Fowler swimming pool with me on hot afternoons, Alice assisting me in my incarnation as Dr. Sly, child magician and escape artist.

I remembered the time she and I convinced our Sunday school teacher that all of the students should read their favorite Bible stories Aloud. The others read David and Goliath or Noah. I read Judges 5, Verse 26, how Jael pounded a tent peg into the head of Sisera, the heathen. Alice read Second Samuel 11, how David spied Bathseba naked and dispatched her husband to the front lines to be slaughtered.

I drove to Fowler’s First Christian Church, where my father had been pastor. The four chandeliers my parents donated in memory of Alice still hang from the white roof of the sanctuary. My mother’s painting of a girl lighting candles at an altar still decorates the east wall.

I sat in a wooden pew and stared above the communion table at the stained-glass window of Christ praying in the Garden of Gethsemane. I had taken collections, said prayers and read announcements beneath that window hundreds of times. They called me “the little preacher.”

I closed my eyes: I am a lanky boy with buzz-cut hair and glasses mended with Scotch tape. My mother wears her most colorful hat and we walk down the church aisle together holding hands as the mourners’ heads turn in unison at our passing. We step to the first row in front of Alice’s open coffin. She is in heaven and we are witnessing: “Alleluia! Where O Death Is Now Thy Sting?”

“I did the first portion of your sister’s funeral service,” said pastor Charles Whitmer when I asked him for his memory of the funeral. “When I finished, your father walked up next to the casket and began talking about Alice. He talked about his relationship with her and how much all of you loved her and he kept his composure the entire time. I remember thinking that no one could do that, no one could have kept his composure like he had, unless Christ was with him.”

During the prayer, I search for Flora Ledbetter, who sits near the back of the church. She is sobbing. Her husband sees me and lowers his eyes. She is not to blame, my parents had said.

I look at my mother, my father, my brother. Their eyes are closed.

My parents are holding hands, tightly.

I look at Alice. They have put too much makeup on her. She hates makeup.

I had kissed her goodbye, the night before, and her skin felt hard. My father had called her “Our Sissie.”

I raise my head and look at the window of Christ in the Garden. The morning sun has turned his robe blood red. Alice’s faith was always so complete. She had once promised that if the communists took over, she would die a martyr. I opened my eyes, walked to the altar, and knelt to pray, but I couldn’t. I waited, and it didn’t come. I looked up at the stained -glass window of Jesus.

“Damn you!” I whispered. They were the words of a 14-year old boy.

I drove to Jones Corner from Fowler by the route Alice had taken that night. Then I drove Ledbetter’s route, three times. On the last trip I jammed on my brakes, imagining that I had just seen Alice on the scooter. The car swerved as it entered the intersection, its headlights cutting a swath across an empty field. I got out of the car and began pacing.

In the four years I lived in Fowler after Alice died, I had never visited Jones Corner. I stepped from the road into the ditch where Alice had been thrown. It was steeply sloped, several feet deep, patched with snow. I stepped on a beer bottle. An old magazine was frozen to exposed grass. I tried to picture the scene: Ledbetter’s car in the center of the road, my motor scooter thrown 66 feet to the side, my sister at my feet.

motor scooter thrown 66 feet to the side, my sister at my feet.

“I remember your sister was lying in the bar ditch about here,” Wes Ayers, Fowler’s deputy sheriff, had told me earlier in the day as he marked the spot on a piece of paper. “At the time, state troopers filed reports only if there was a fatality, and I asked the state trooper if he was going to do a report on your sister. He said, No.’ ”

” ‘Don’t you see that big cut on that little girl’s leg?’ I asked. ‘Well, it ain’t bleeding at all and that can only mean one thing: she’s got to be bleeding inside.’ After I told him that, he got out his clipboard.”

The thought of Alice lying among strangers as they speculated about the odds of her living enraged me. It had taken almost an hour after the accident to get Alice to the 37-bed Pioneer Memorial Hospital, only 22 miles away. The emergency room report, brief and routine, didn’t explain the long gap; it said she died of shock.

She arrived at 8:00 p.m., awake and complaining of pain: “Pt ventilating when first seen. B/P 90/60 — gradually dropped. Given Demerol 75 mg. For pain. Pt went into shock & coma.”

After Alice lapsed into unconsciousness, they finally started IVS in her right arm and ankle, suctioned her throat, massaged her heart, gave her adrenaline.

“Pt never regained consciousness. Expired 9:30 p.m.”

Years before my sister died, I shot a rabbit a few yards from the Fowler Cemetery, east of town and set amid towering Chinese elm trees. I had spooked the cottontail from a woodpile and it ran up an embankment, where it froze. I blasted its entrails across the snow.

I thought about the rabbit and my clear memory of it when I drove into the cemetery. But I could not recall a single details of my sister’s grave side service.

It was almost midnight and the moon illuminated the tombstones. It was snowing gently. I walked to the headstone I believed was my sister’s, but it wasn’t. I slowly walked row by row, examining each headstone, seeing the names of people I had known in Fowler. Clouds began to block the moonlight and it seemed to get colder.

It is embarrassing to say, but I suddenly felt afraid, as if I were intruding.

For two decades I had lived without thinking of Alice. I thought, “I knew her only 14 years. She has been here for 19.”

I couldn’t find the headstone, so I shined my car’s headlights into the cemetery. It was so cold now that I began to speed up my search. It struck me that Alice would not let me find her! I ran, faster and faster, glancing at each name. A sense of desperation shot through me. Suddenly, I caught myself. The image of me, frightened and racing through the Fowler Cemetery at midnight, was ludicrous. I would return tomorrow.

That night, voices outside my motel door awakened me from a dream. I lay in bed afraid to move, an emotion I had not felt since childhood. In my dream, I had been jogging. It was dark and a car began to follow me. It forced me down an alley blocked by a tall chain link fence. A gang of boys got out of the car. They pulled knives from their coats. I scrambled up the chain link fence, but as I reached the top it curled backward slowly, lowering me toward them. Just as they were about to reach me, they turned and grabbed someone else from the shadows. They stabbed and stabbed and stabbed, until the person was dead. Then they turned and pointed their bloody knives toward me.

I found Alice’s grave without trouble the next day. “Alice Lee Earley, February 13, 1949. June 14, 1966. A lovely Daughter.”

I wanted to talk to her, but I felt foolish. If all there ever was of Alice was still in that grave, she would not hear me anyway. If life and death are miracles though, I could have talked to her as easily from Washington as Fowler. I placed a bouquet of daisies before her headstone.

A farmer drove by in a pickup. He glanced at me; I was ashamed at my embarrassment.

I stood for the longest time. I wanted a sign. Some little miracle — hearing Alice’s voice in my head, perhaps. But I heard only the silence that reaffirmed her refusal to welcome me. I thought that the daisies would freeze that night. I hoped the caretaker would leave them at least through tomorrow. Alice gets flowers so seldom, I thought. A sadness came to me: My trip was for nothing.

But as I returned to the car, the anger rose in me again — this time anger at Alice. I walked back to her grave and placed my hands on the stone. I drifted between talking and thinking. “Okay, you died, but things weren’t so great here either. I did move into your room. I got your dresser. I got your guitar. But things changed after you died. Night after night I lay in your bed listening to Mom and Dad cry.” ‘If only we had bought her a car! If only we hadn’t bought the Honda!’ When they started the tranquilizers, I was terrified they, too, would die.”

“You left me, Alice! You died on my motorcycle! You always were so careful! I was the reckless one, everyone knew that! Why didn’t I take the Honda’s keys with me to church camp?” I began to cry: “Why did you have to die, Alice? Why not me?”

I turned to leave, but as I walked to the car I felt a calm. I returned to the grave and sat in the snow. Eventually, I began to talk. I told Alice that I had left Fowler for college, that I had married at 20. I talked of the newspapers where I had worked, my house in Virginia, my three children. I said my oldest son, Stephen, had scored four points in last Saturday’s basketball game.

I told her that I teach Sunday school, but that the “little preacher” had died with her. Even today, I think of her and a naive rage at God wells up. My faith is unclear to me.

I told her that my three-year-old daughter Kathy looks a lot like her, which makes me happy. At the times when I have been the happiest, however, I have sometimes looked at Kathy and felt suddenly sad at the inevitability of despair. I talked until I had nothing left to say and then I sat. I reached down and touched her grave marker. It wasn’t enough. I kissed the stone. “I love you, Alice. I always have.”

I tracked Flora Ledbetter to the western slope of the Rockies. She and her husband, a teacher at Fowler High, had left Fowler a year after the accident. He was later killed in an airplane crash. Her second husband died of cancer. She married again and moved here. I wondered if her husband knew.

“I don’t know if you will remember me or not,” I said.

“I remember you,” she answered. “What do you want?”

What I wanted from Ledbetter was remorse. I wanted her to say she was sorry. I wanted her to accept the blame I had assigned to her for 19 years. It turned out she wanted absolution from me. The accident had devastated her at the time, she told me. She wondered why she had lived and Alice had died. She sobbed for days; she couldn’t sleep.

Three days after the accident, she returned to Jones Corner. By then a stop sign had been installed on the road Alice was traveling.

“If anyone was to blame,” Ledbetter said, “It was your sister. That’s where the state put the sign, didn’t they?…The worst part was that your parents sued me. The Bible says Christians shouldn’t sue each other. Your father knew that. I didn’t care about the money, but they were trying to prove that I was responsible. That wasn’t fair.”

I had not expected this. Like me, Ledbetter was angry — but at the state, at Alice and at my parents for filing a $25,000 wrongful death suit against her.

Suddenly, I was on the defensive.

I told her my parents sued because her insurance company had refused to help pay for the funeral and had harassed them repeatedly to settle without my parents initially ever asking for a cent. A life insurance representative had come to our house before the funeral and declared that Alice’s life was worth only $500. I had never seen my father so enraged.

The case eventually settled out of court for about $10,000, without Ledbetter admitting or denying guilt. I still remember the talk around town: My father, the minister, profiting from Alice’s death. “Blood money,” one Fowler gossip called it.

“The state trooper told me that this was one of those truly unavoidable accidents,” Ledbetter said. “Your folks sued me anyway.”

My tone changed.

“I drove to that corner, ” I said coldly. “I retraced your steps and I could see perfectly.”

“There were weeds there and a big mound of dirt back then that made it hard to see. I think there was an irrigation well, too. I can’t remember.”

“I hated you when I was growing up. I covered your husband’s photograph in the school yearbook with white tape.”

She was quiet. “How do you feel now?”

I hesitated. “I don’t hate you anymore. It was an accident. I guess it was no one’s fault.”

“I’m glad we talked,” she said.

I went to a bar.

My mother had put the family scrapbooks out for my arrival. She was eager to talk about Alice. My father was reluctant. Late that night, we finally began. “We were in the emergency room with Alice,” my mother said. “She kept saying to me, ‘Mamma, Mamma, I’m gonna die. It hurts. I’m gonna die,’ and I said, ‘No darling, it’s okay. They are going to save you. You are going to be okay.’ ”

My mother took off her glasses and wiped her eyes.

“They didn’t do a thing for her,” my father said. “They cut her foot and put some kind of line in it, but it was leaking out all over the floor. Then they got into an argument because one of them didn’t want to put a tube down her throat. She would have been just as well off if they had left her in the ditch, maybe better. The ambulance ran out of gas on the way to the hospital.”

That explained the delay in Alice’s arrival at the hospital. I thought of my parents standing helpless as Alice died.

“Why didn’t you sue them?” I asked.

“Who?” asked my father.

“All of them!”

“I’m sure that they did all that they could,” said my mother. “They didn’t know as much then as they do now.”

“But you sued the Ledbetters.”

There was a long silence.

“The last time I saw Mrs. Ledbetter,” my father said, “she said it was God’s will’ that Alice died.”

“It was just so unfair,” my mother said. “Here was this big insurance company and we were so little… Do you know when Ledbetter’s first husband died? He was killed February 13 — on your sister’s birthday. When I first heard it, I felt it was retribution. Your father never felt that way, but I did. Then I decided that was wrong.”

“Everything that could have gone wrong did,” my father said. “Both doctors in Fowler were out of town that night.”

“Alice was supposed to be at work,” my mother said. “But she had traded hours with another girl. I got so mad at that girl that I couldn’t stand seeing her. I was mad at the Ledbetters. I was mad at the superintendent’s wife because she didn’t come to the funeral. I was mad at the sheriff’s wife for not calling us when the accident happened so we could have gotten there in time to send Alice to Pueblo. I was mad at the doctors. But after a while, you realize that it doesn’t help. Nothing can bring Alice back.”

“How about God?” I asked. “Did you blame Him?”

My father shook his head. “No, I never felt that way.”

On my first night home in suburban Virginia, Kathy woke me in the night and I carried her downstairs to the rocking chair. We sat long after she fell asleep and I thought of Alice.

“She’s gone,” my mother had said. “What’s the use in blaming?”

I had told Flora Ledbetter that I didn’t blame her for Alice’s death. And I had meant it. Still, if she had left a minute earlier, taken a different route, Alice would be alive. I don’t blame Ledbetter, but I do blame Ledbetter. I don’t hate her, but I do hate her.

Job demanded of God: Why are the innocent slaughtered? “Then the Lord answered Job…Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth? Tell me, if you have understanding.” I don’t, I thought. I don’t understand.

I closed my eyes and thought of Alice.

My mother, father, brother, Alice and I are in our backyard in Fowler. It is a summer Sunday night, near dusk. My mother sits in a brown lawn chair next to my father in his folding chaise. I sit with my brother a few steps away in the long grass holding our dog, Snowball. Alice stands at the grill, her back to us. She wears navy blue shorts and a white blouse. She is barefooted. Smoke and the scent of cooking hamburgers rise from the grill. Alice turns. The sun has reddened her face. The wind has uncurled her hair. She looks at me, and she is laughing.