(3-9-16) If you think the federal government should do something to fix our mental health care system but you really can’t agree or don’t know what needs to be done then you should be pleased with the much anticipated draft version of The Mental Health Reform Act of 2016 that a bipartisan group of U.S. Senators released yesterday. (Click HERE for text of the staff discussion draft.)

It pretty much ignores the changes that Rep. Tim Murphy (R.-Pa.) is proposing in his Helping Families In Mental Health Crisis Act and also snubs much of what the House Democrats offered in the Comprehensive Behavioral Health Reform and Recovery Act of 2016 .

“The bipartisan draft legislation works to bring our mental health care system into the 21st Century by embracing mental health research and innovation, giving states the flexibility they need to meet the needs of those suffering, and improving access to care,” Sens. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.), the leader of the Senate Health Committee (HELP), along with Democrat Sen. Patty Murray (Wash.) and Sens. Chris Murphy (D-Conn.) and Bill Cassidy (R. La.) declared in a joint press release.

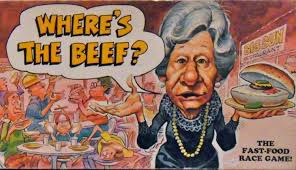

Really? That’s tall praise for a bill that contains mostly sizzle and no steak.

The Senators agreed with both Murphy and House Democrats that appointing an Assistant Secretary of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Treatment inside the Department of Health and Human Services to elevate the importance of mental health care in the federal government is a swell idea. They also like the Democrats’ proposal about creating an “Office of Chief Medical Officer” — inside SAMHSA that would be run by a doctor. And they think it would be wonderful if the federal government created a telephone “routing service” that individuals could call to find out what services are available in their communities.

Services? Did someone say services?

When it comes to what those services should be or how those services are going to be financed, the Senators punted. That would be the job of the new Asst. Sec. to figure out and report back to them. Meanwhile, they deleted specific budget amounts at several points and instead inserted the political euphemism “such sums as necessary.” Oh, they also spent a lot of time going through the current federal language and changing ‘‘substance abuse’’ to ‘‘substance use disorder.”

Assistant Outpatient Treatment, the lightening rod in Murphy’s bill that his supporters and his opponents have been bumping heads over for nearly two years, was pretty much ignored, except that the Senators thought that it would be a good idea to study it some more.

How about changing the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA, that has been another boiling point in the pro-Murphy/anti-Murphy debate? Yeah, the Senators think it would be a good thing to study that too.

There is no mention of Murphy’s efforts to restrict the Protection and Advocacy for Individuals with Mental Illness Act (PAIMI) program and no mention that I could find about encouraging states to add a “need for treatment” to involuntary commitment laws.

Nor is there any specific mention of supporting the Democrat’s call for spending $20 million to promote Mental Health First Aid, a program that teaches member of the general public how to recognize mental illnesses; and no talk of such programs as Open Dialogue, a Finland program that focuses on respecting the decision making of the patient. (Although the Senators did take the bold step of agreeing that the government needs to listen more than it has in the past to people who actually have lived experience. Suggestion: if that’s the case, then the House and Senate need to begin calling them as witnesses.)

As you might expect, Rep. Murphy was not pleased.

“When it comes to transforming the hopelessly failed federal mental health system, we can make a deal or make a difference. The House bill will make a profound difference by emphasizing early treatment for serious mental illness and psychiatric intervention for families in crisis. To abandon House reforms supported by a bipartisan coalition of 185 members would be tantamount to abandoning patients with seriously mental illness and those who have devoted their lives to care for them.”

The Treatment Advocacy Center, which had been pushing hard for passage of Murphy’s bill, agreed. “If this were to pass as is, it would be of no benefit to (people with) severe mental illness,” John Snook, TAC’s executive director told reporter Shannon Muchmore with Modern Healthcare.

Paul Gionfriddo, president and CEO of Mental Health America, said the bill has a good foundation but lacks important details and “has a long way to go.”

The National Alliance on Mental Illness did not immediately release a statement but I was told it was eager to work with senate staffers to address some of its concerns.

Which brings us to the only good news about the bill. It sets the stage for a conference with the House during which both sides can begin shaping a new compromise bill.

One well-respected Hill advocate told me that everyone — including me — was overreacting yesterday. “This is how the Senate HELP Committee operates. The Senators have to have 100 percent consensus, which is not easy on a Committee where the membership spans from Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren on the left and to Rand Paul and Tim Scott on the right. Anything controversial had to fall out of the bill.”

Yesterday’s maneuvering reminded me of when I served on a contentious state task force after the Virginia Tech shootings that was asked to recommend changes to our state’s “imminent danger” involuntary commitment law. Those meetings were filled with lots of often angry banter and bluster. In the end, three proposals were voted on. One proposal called for doing nothing and another was to lower the criteria so much that Virginians would have few protections. Then there was a middle ground that pleased neither side. You guessed it, the task force eventually agreed on the middle ground. I was rather naive and when I spoke to both sides, I was surprised to learn that neither had expected their version to win a final recommendation. It was posturing.

The Senate has now set a low standard and cast Murphy’s bill at the other end of the debate. So far, Rep. Murphy has dug in his feet about several key changes. The question now is: Where will this all end up?

Once the Senate and House agree on a compromise, that bill will move to both chambers for a vote and then, if passed, to the White House to be signed into law.

Put simply, there is still more to come.

“In the current climate, any bill that gets bipartisan support is going to be fairly vanilla,” another insider told me yesterday.

That’s a pretty low bar when people are going untreated, our jails and prisons are filling up with individuals who are sick, and thousands of others in the midst of a crisis can’t get help.

But then, that’s politics.