(3-22-16) An Eastern State Hospital employee was “astonished and distraught” when she opened a desk drawer last August and discovered that a Virginia judge had ordered Jamycheal Mitchell to be sent from a Portsmouth jail to the mental hospital to be evaluated.

The judge’s order had been issued more than three months earlier but had been overlooked in that desk drawer until she discovered it — five days after Mitchell had died of a heart attack caused by starvation while in jail.

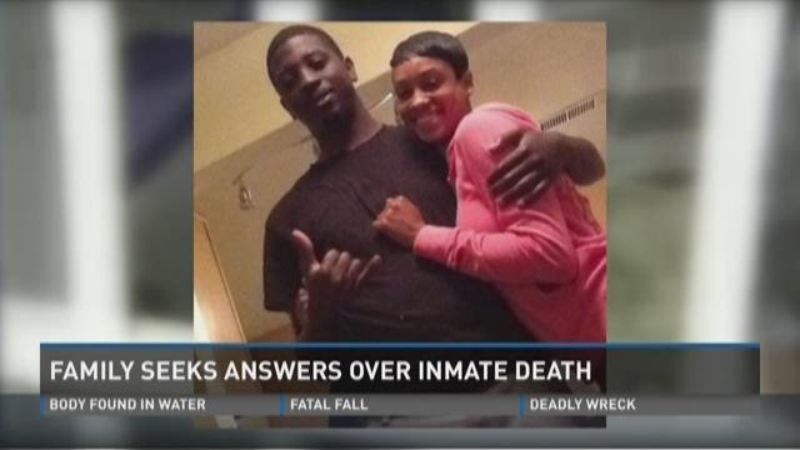

That disclosure is one of several troubling admissions revealed yesterday when the Virginia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services finally released an edited version of the investigation that it conducted into the August 19, 2015 death of Mitchell, a 24 year-old, African American inmate with a serious mental illness who’d been charged with petty larceny and trespassing after stealing $5 worth of snacks from a convenience store.

Last week, I posted a blog that questioned why three Virginia agencies responsible for investigating the Mitchell tragedy hadn’t made public their investigations. The DBHDS released copies of its 29-page report, minus the identities of the employees who investigators questioned, without comment based on separate Freedom of Information requests filed by Sarah Kleiner, an investigative reporter at Richmond Times Dispatch, and by me.

When called by reporters for comment, I said that I was “furious and outraged” by the report. “Jamycheal Mitchell was lost in plain sight because of incompetency and indifference. This kid died because no one in that jail and no state mental health official did anything to help him. Shame on them. Imagine if he was your son. Now there will be lots of finger-pointing and lawyering up, but no real changes. That’s been our sad history in Virginia. This is because officials will blame the victim, as they did in the Natasha McKenna case, and legislators will not put any more money into mental health services.”

What did the internal investigation reveal?

On May 21, 2015, a judge signed a Competency Restoration Order, that was supposed to be mailed to Eastern State Hospital, alerting it that Mitchell needed to be admitted into that hospital. Investigators could find no record of that order ever being sent to the hospital. That was the first mistake.

On July 31, 2015, the court discovered that error and successfully faxed that same judge’s order to the hospital where it apparently was tossed into a desk drawer and not entered into the hospital’s record system. It sat there until a clerk discovered it five days after Mitchell was already dead. Another mistake.

But there is more. In earlier FOIA requests that I made, the DBHDS acknowledged that it had hired an employee in January 2014 to work ten to fifteen hours per week inside the Portsmouth jail because the state “was having challenges with the HNNSCB (Hampton Newport News Community Services Board, which delivers health care in the area) not quickly and consistently getting to the jail to triage restoration referrals.”

That means jailed inmates with mental health issues were sitting in cells without being seen promptly and transferred to the state hospital. Now remember, this employee was hired more than a year before Mitchell was found dead so the HNNSCB and the DBHDS were clearly aware that jail boarding had become a problem in Portsmouth.

Yesterday’s report revealed that this employee apparently did not interview Mitchell. Ever. No one from the state did, as far as I can tell from the edited report.

On July 30th, jail officials became so alarmed about Mitchell that he was sent to the emergency room at the Bon Secours Maryview Medical Center. When he arrived, he refused treatment and was returned to the jail. Jail officials asked that an “emergency assessment” be done. The next morning, Mitchell was taken back to court and officials there realized that the judge’s initial order (sent on May 21) had not been received by the hospital. That led to the court faxing an order to the hospital. Meanwhile, the DBHDS employee, who was supposed to check on Mitchell, went to the jail on the morning of July 31st, while Mitchell was in court. She waited for forty minutes and when he hadn’t returned to the jail, she left without seeing him. She later told investigators that because the court had faxed an order to Eastern State, she didn’t feel he fell under her jurisdiction. He was not her responsibility.

The report reveals that the nurses at the jail, who worked for the for-profit company, NAPHCARE, told investigators that all of their statements and information had been sent to the company’s headquarters in Alabama. Because the names of those being interviewed were deleted from the released report, it is impossible to tell if those nurses cooperated with investigators, but it appears that the state did not ask NAPHCARE for any information. Why? The public deserves to know what this private company did and didn’t do inside that jail.

There was one curious statement in the report by someone employed in the jail. That person was quoted as saying that no one realized Mitchell was not eating because “other incarcerated individuals stated that Mr. Mitchell would ask them for their food…(and) Mr. Mitchell’s food trays were empty indicating he was eating.”

I find it incredible that an inmate’s caloric intake would be determined based on his food trays being empty and other inmates saying that he was eating regularly rather than a physical examination. Had one been done, it would have revealed that Mitchell had lost more than 10 percent of his weight — some 36 pounds — and that he was starving himself.

(Often times inmates who are delusional refuse to eat because they believe they are being poisoned. One solution is to deliver pre-packaged food to that inmate, Joanna Walker, a local NAMI leader told me.)

There will be much finger-pointing and hand-wringing now but what really will be done? It is an important question because there are currently more than 7,000 inmates in Virginia’s local and regional jails. DBHDS hospitals have a census of about 1,500, so our jails hold more than our hospitals. That is true in every state. When Mitchell died, there was a waiting list of 34 inmates ahead of him. How long had those inmates been waiting and under what conditions?

The report released yesterday noted that the employees at Eastern State, who were supposed to log in court orders, were behind because of a staff shortage at the hospital. At least two employees, who used to help out, had left the job and no one had been hired to fill those spots. Mitchell’s death is a result of what happens when our state continues to not adequately finance our mental health system. His death also is another reminder that jails are no place for persons who are mentally ill. Mitchell’s death, and the earlier death of Natasha McKenna in Fairfax County, are evidence of that.

Unfortunately, yesterday’s report does not answer the most important question about Mitchell’s death. How is it possible that he was allowed to starve himself to death? The state seems satisfied to let that question go unanswered. There is no mention in the report that the state will demand an explanation from NAPHCARE. That’s wrong!

Now that the state has released its report, the Office of State Inspector General needs to release its probe. It is supposed to be independent of the DBHDS, although recent actions by the OSIG have raised questions about its independence.

The last IG to criticize the DBHDS was G. Douglas Bevelacqua who resigned in protest after his boss soft peddled one of his reports after talking privately to DBHDS officials. When I asked Bevelacqua his opinion of yesterday’s DBHDS report, he wrote in an email:

Let’s be clear. It is inexcusable that a mentally ill person should starve to death while incarcerated in a Virginia jail. There is no explanation that will ease the shocking truth that the Hampton Roads Regional Jail in Portsmouth, and the mental health providers from several organizations – including the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services (DBHDS), the H-NN CSB, and NAPHCARE, Inc., — failed to care for Jamycheal Mitchell.

Bevelacqua questioned why his former agency still has not released its investigation seven months after Mitchell’s death.

The third Virginia agency that should be investigating Mitchell’s death is the disAbility Law Center, which is Virginia’s Protection and Advocacy for Individuals with Mental Illness Program. It was created by the federal government to insure persons are not being abused in institutions. Sadly, no one from the Center has stepped forward to comment about Mitchell’s death.

Given that the disAbility Law Center appears uninterested in demanding answers, let’s hope the IG’s office has the backbone to do its job.

Jamycheal Mitchell’s family and the public deserve to know what happened in that jail.