Officers help evacuate airport passengers during mass shooting at Fort Lauderdale airport that killed five. (Photo courtesy of Daily News)

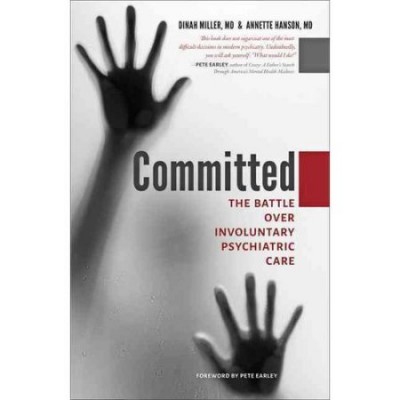

(1-8-17) Not everyone agreed with my grim Monday blog about mass murders and my blaming of the dangerous criteria that often is used in deciding who can buy and possess a firearm or be involuntarily admitted into a hospital. Among those with a different point of view was Dr. Annette Hanson, co-author of the book, COMMITTED, The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care. Dr. Hanson is an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. She also is a coauthor of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrist Discuss Their Work, and she contributes to a blog by that same name.)

Mass Shootings, Mental Illness, and Public Safety

By Dr. Annette Hanson

Would changing the legal definition of dangerousness for involuntary treatment prevent mass shootings?

In a word, no.

A mass shooting, which is commonly defined as the killing of four victims in a public place, is a relatively rare event.

In 2012, the year with the highest number of mass shootings, there were only seven incidents. Our ability to predict such rare events is tenuous at best. Prediction could be improved if the pool of all potential shooters could be narrowed down a bit, but to date no useful “profile” or typical characteristics of a mass shooter have ever been identified. While some mass shooters have had contact with mental health care prior to their crimes, as many as thirty percent have had no mental health history whatsoever. The strongest consistent characteristic of a mass shooter is male gender, but public gun policy based on gender is obviously impractical.

Even for perpetrators with a history of mental health treatment, changing the legal definition of dangerousness for civil commitment does not help clinicians decide who should or should not be admitted against their will.

An assessment of dangerousness is situation dependent, meaning that any legal standard still requires a clinician to apply the law to the facts of a given case. No legal standard can anticipate every hypothetical situation, and clinical decisions about dangerousness are sometimes influenced as much by the clinician’s personal experience and training as by the law.

If a doctor has had a case with a violent outcome involving a left-handed redheaded patient from Scandinavia, you can bet that he or she will be more cautious the next time he/she treats a left-handed redheaded patient from Scandinavia. A cautious clinician will interpret “dangerousness” liberally regardless of the statutory definition, and leave the legal interpretation up to a committing judge.

Given the scarcity of inpatient beds now, loosening the commitment standard will also not assure that all those who are eligible actually get admitted. In Maryland, ninety percent of patients admitted against their will are committed to the hospital following a hearing. That’s a high average because only those who are assessed as “most” dangerous are ever held for a hearing. Others never get that far in the process.

Clinical discretion is most accurate when predicting safety, since safe behavior is much more common.

Gun violence generally is more common than mass shootings, but guns are not the weapon of choice for people with serious mental illness. The most common type of violence committed by formerly committed patients involves pushing, shouting, hitting, or making threats–behavior that is certainly frightening but which usually does not result in physical injury or even actual physical contact.

In very rare cases—the kind of case I usually see as a forensic psychiatrist—when a victim is killed by a person with mental illness there is usually not a gun involved. Insanity acquittees who have been violent use whatever weapon is at hand, like a kitchen knife or heavy object, or even bare hands. Unless the weapon belongs to another household member, actively psychotic individuals rarely have the organizational skills to go out and purchase a legal weapon. In contrast to popular opinion, the general public has little to fear from people with serious mental illness. Active psychotic symptoms usually cause a person to withdraw from public places out of fear; family members, rather than the general public, are those at risk in the rare cases of psychotically motivated violence.

But isn’t there something we can do about mass shootings?

Yes!

We can separate the issues of access to weapons and mental illness.

Most states already restrict gun purchases by people with certain criminal convictions or histories of domestic violence. What most states don’t have is a way to remove a weapon–legal or otherwise–from someone who has exhibited violent behavior without a past legal or mental health history. California has adopted a new law, known as a Gun Violence Restraining Order (GVRO), which allows a court to temporarily confiscate a weapon from any individual who exhibits dangerous or threatening behavior, without any determination of mental illness. A GVRO temporarily bars future purchases. When a gun restraining order is granted, the judge can issue a warrant allowing police to search for and confiscate any weapon in the respondent’s possession. The initial order lasts for 21 days but can be extended up to one year.

Gun violence restraining orders would allow a court to remove weapons from those most likely to use them: angry or disgruntled individuals with active substance abuse issues and recent life stressors. Unfortunately, only a handful of states currently have these laws.

There are good reasons to restrict access to weapons for certain individuals, but the most important reason has nothing to do with public safety. Connecticut’s gun violence restraining order has been associated with a significant drop in suicide rates. Conversely, states that rate high in gun ownership also tend to have higher suicide rates. Ultimately, suicide prevention is the strongest argument for any change in current law.