(11-24-17) This is one of the best stories about homelessness that I’ve read. Thank you at The Washington Post for writing it. Among the take-aways: most of these folks had been through recovery programs yet have not become engaged in treatment? Why?

Another take-away: a homeless woman who has been diagnosed with a serious mental illness agreed to see a psychiatrist when she spoke to a treatment team but disappeared when a psychiatrist came looking for her. She preferred to continue “self medication.”

And finally, the quote: “Most of our folks think they will die alone, that their future is canceled. Bringing hope is more important than any medicine.” It’s a great reminder that it takes a personal connection to connect in a meaningful way with another person.

These are all truths that I learned personally when I spent time with homeless workers in Washington D.C.’s Georgetown neighborhood with Gunther Stern, who runs Georgetown Ministries street outreach team.

In the woods and the shadows, street medicine treats the nation’s homeless

By The Washington Post on Thanksgiving Day.

Nurse Laura LaCroix was meeting with one of her many homeless patients in a downtown Dunkin’ Donuts when he mentioned that a buddy was lying in agony in the nearby woods.

“You should check on him,” said Pappy, as the older man is known. “But don’t worry, I put him on a tarp, so if he dies, you can just roll him into a hole.”

LaCroix called her boss, Brett Feldman, a physician assistant who heads the “street medicine” program at Lehigh Valley Health Network. He rushed out of a meeting, and together the two hiked into the woods. They found Jeff Gibson in a fetal position, vomiting green bile and crying out in pain from being punched in the stomach by another man days earlier.

Feldman told him he had to go to the hospital.

“Maybe tomorrow,” Gibson replied.

“Tomorrow you’ll be dead,” Feldman responded.

Months later, the 43-year-old Gibson is still in the woods, but this time showing off the six-inch scar — for a perforated intestine and peritonitis — that is evidence of surgical intervention. He greets Feldman warmly. “You’re the only person who could have gotten me to the hospital,” he says. “You’re the only person I trust.”

ROUGH SLEEPERS: It’s Our Duty To Go Out And Find Them

Pappy and Gibson are “rough sleepers,” part of a small army of homeless people across the country who cannot or will not stay in shelters and instead live outside. And LaCroix and Feldman are part of a burgeoning effort to locate and take care of them no matter where they are — whether under bridges, in alleyways or on door stoops.

“We believe that everybody matters,” Feldman says, “and that it’s our duty to go out and find them.”

Most of the time, members of his team provide basic primary care to people who live in dozens of encampments throughout eastern Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley. During their street rounds, they apply antibiotic ointment to cuts, wrap up sprains and treat chronic conditions such as blood pressure and diabetes.

But they also help people sign up for Medicaid, apply for Social Security disability benefits and find housing. Three or four times a month, they deal with individuals threatening to commit suicide. After heavy rains, they bail out “the Homeless Hilton,” a campsite under an old railroad tunnel that frequently floods — and where two rough sleepers once drowned. Many days, they simply listen to their patients, trying also to relieve emotional pain.

Street medicine was pioneered in this country in the 1980s and 1990s by homeless advocates Jim O’Connell in Boston and Jim Withers in Pittsburgh. Yet only in the past five years has it caught fire, with a few dozen programs becoming more than 60 nationwide. A recent conference on the topic in Allentown drew 500 doctors, nurses, medical students and others from 85 cities, including London, Prague and New Delhi. Most programs are started by nonprofit organizations or medical students.

Even as it comes of age, street medicine faces new challenges. A younger set of leaders is less interested in cultivating a bleeding-heart image than in establishing the approach as a legitimate way to deliver health care not only to the homeless — whose average life expectancy is about 50 — but also to other underserved people. Backers say street medicine should be considered a subspecialty, much like palliative care is, because of the unique circumstances of treating its target population.

Saved $3.7 million by providing street medicine

Proponents also are pressing for much more financial support from hospitals, which can benefit greatly when homeless individuals receive care that helps keep them out of emergency rooms. Feldman’s program — which includes the street team, medical clinics in eight shelters and soup kitchens, and a hospital consultation service — has slashed unnecessary emergency room visits and admissions among its clientele. The result, to the surprise of Lehigh Valley Health Network officials, was a $3.7 million boost to the bottom line in fiscal 2017.

Perhaps the biggest issue facing street medicine, however, is figuring out how to provide more mental-health services. About one-third of homeless people are severely mentally ill, and two-thirds have substance-use disorders. Long waiting times for psychiatric evaluations delay needed medications and, in some cases, opportunities to get housing.

Psychiatrist Sheryl Fleisch is working on that problem. In 2014, she founded Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s street psychiatry program, one of a few such initiatives in the country. Every Wednesday morning, Fleisch and several medical residents visit camps in Nashville, handing out shirts, blankets — anything that can build trust.

Then they split up to talk one-on-one with people waiting on park benches, at bus stops and in fast-food restaurants, providing a week’s worth of prescriptions as needed. Fleisch says these homeless patients seldom miss an appointment.

Many “have been thrown out of other programs or are too anxious to go to regular office sessions,” she said. “We have some patients who will get up and sit down 15 times during our appointments. We don’t give up on them.”

On a muggy fall morning, Feldman’s team makes its way from the Hamilton Street Bridge in downtown Allentown to a swath of mosquito-infested woods between the railroad tracks and the Lehigh River. A few blocks away, an extensive redevelopment project, complete with a luxury hotel and arena for the minor-league Phantoms hockey team, is revitalizing parts of the long-depressed area.

Bob Rapp Jr., who has worked extensively with homeless veterans and knows the location of many campsites, is the advance man. “Good morning! Street medicine!” he calls out.

Feldman carries a backpack full of medicines. LaCroix uses her “Mary Poppins bag” to try to coax people out of their tents: “We’ve got supplies — socks, toilet paper, tampons!”

A thin woman with striking blue eyes pops out of a tiny tent, pulling at her wildly askew blonde hair as she glances in a mirror propped against a tree. Her toenails are painted gold. A Phillies cap and a Dean Koontz book, “Innocence,” sit on one of her two chairs.

“Tampons!” exclaims the woman, who identifies herself only as Duckie. “I just turned 60. I don’t think I need tampons!” She hugs LaCroix, with whom she bonded after the nurse helped her get new clothes and emergency treatment for a virulent, highly contagious skin infestation called Norwegian scabies.

Feldman kneels in front of Duckie with his stethoscope to check her lungs; the last time he saw her, the longtime smoker had bronchitis. No breathing problems this time, but Feldman tells her he wants a psychiatric evaluation. If the doctor confirms that she has bipolar disorder, depression or post-traumatic stress disorder — all diagnoses Duckie says she has heard over the years — she will be able to get the drugs she needs and perhaps transitional housing.

“I self-medicate,” she shrugs. But she likes the idea of moving inside with winter coming.

“It stinks out here,” she says. “It’s cold. I have to watch out for rats and raccoons and people.” She agrees to see a psychiatrist — a volunteer who comes out once a month — at her tent the following week.

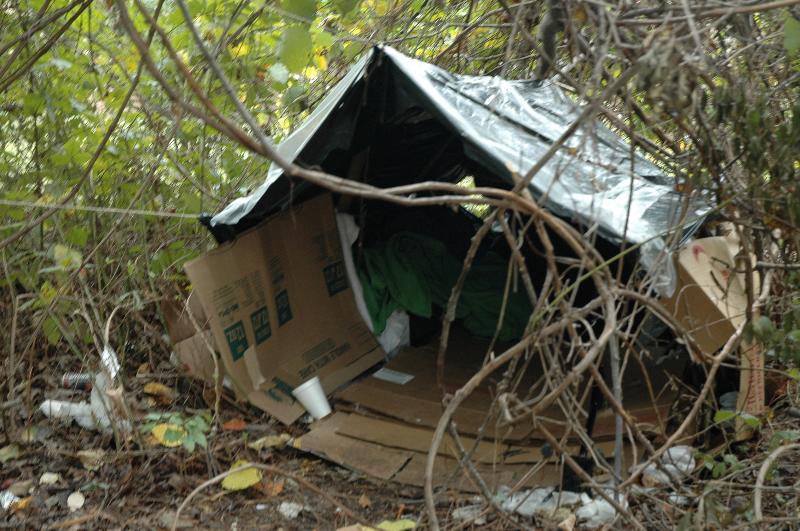

Later in the day, the team goes to see a favorite patient. When the group approaches his plastic-covered hut in the woods, Mark Mathews frantically orders them to stop. “I don’t want to be caught with my pants down!” he yells from within.

Moments later, khakis on, the 57-year-old emerges. The son of a successful Allentown actor, the grey-bearded Mathews spent years playing Santa Claus in malls. He also worked for a high school theater department and in the 1980s was part of a local cable comedy show, “Sturdy Beggars.”

He became homeless after having a falling out with his sister four years ago. “The money ran out, and I couldn’t get another job,” he says.

LaCroix takes his blood pressure. The reading is high, something Mathews blames on not having taken his blood-pressure medicine that morning. The team will be back in two days to do a recheck, which is fine with him. “I enjoy their company,” he says.

Once, LaCroix carried a mattress across an old railroad trestle and up a steep hill to deliver it to his hut. Like other patients out here, Mathews has the team’s cellphone numbers. He frequently texts LaCroix to tell her jokes or alert her to someone’s possible health problem.

Mathews is sure his life has purpose. “I try to help other people,” he says. “I lend people phones if they don’t have them. I help them get to their appointments. I should be nominated for sainthood.”

ABOUT 550,000 WERE HOMELESS IN 2016

About 550,000 people in the United States were homeless in 2016 on a given night — according to the most recent estimate by the Department of Housing and Urban Development — and about a third of them were sleeping outside, in abandoned houses or in other “unsheltered” places not meant for human habitation. In Santa Barbara, Calif., so many people live in their cars that the local street medicine team provides care in automobiles.

Federal and regional estimates for the number of homeless people in the Lehigh Valley — which includes the cities of Allentown, Bethlehem and Easton — range from more than 700 to almost twice that number. But that’s likely a big undercount.

A research study of people who sought care at three area emergency rooms during the summer of 2015 and the following winter identified 7 percent as homeless. Feldman, who led the study, said the finding suggested that more than 9,200 of the health system’s emergency room patients were homeless sometime during the year — in communities with no permanent emergency beds for couples and fewer than two dozen for women.

The LVHN Street Medicine program, which he founded, takes care of about 1,500 people a year. Since 2015, it has pursued its mission relentlessly, taking laptops into the woods to get homeless patients insured, usually through Medicaid; today, 74 percent have coverage. Over the same period, emergency room visits by the program’s patients have fallen by about three-quarters and admissions by roughly two-thirds.

It has taken Feldman years to get to this point. In high school, he began lifting weights after getting into a car accident and fracturing three vertebrae. In 2000, as a freshman at Pennsylvania State University, he won the National Physique Committee teen championship.

“It gave me laser focus, but I was the only person who was helped,” he said. “It was very unfulfilling, and I decided that whatever I did after that would be different.”

His close collaborator is his wife, Corinne Feldman, a physician assistant who is an assistant professor at DeSales University. When they first moved to the Lehigh Valley in 2005, the couple wanted to work with the homeless but couldn’t find them — until realizing they were in campsites in the woods. These days, one encampment is even in the shadow of a defunct Bethlehem Steel facility.

The Feldmans started by setting up free clinics in shelters where they worked without pay. But a 2013 Boston conference on street medicine sharpened their focus. They would go to wherever the homeless were.

“We thought, ‘This is all we want to do with our lives,’ ” he recounted.

By then a physician assistant at Lehigh Valley Hospital, Brett Feldman got a grant from a local philanthropy, the Dorothy Rider Pool Health Care Trust, that allowed him to do street medicine one day a week. Over time, he received more grants, as well as backing from the health system to set up a full-time street medicine program. It launched in 2014.

There have been numerous disappointments and heartbreaks:

Two patients at an encampment in Bethlehem froze to death. A man with third-degree burns from sleeping on a heating vent fled rather than have his badly infected lower leg amputated. And before the psychiatrist could come out, Duckie disappeared.

At the same time, there have been poignant victories. When a 50-year-old man, living in a drainage pipe, was given a diagnosis of advanced colon cancer, he declined treatment but eventually was able to move into an apartment, where the street-medicine team provided him palliative care. When his symptoms worsened and Feldman said it was time to go to hospice, the man replied, “First, I have to clean up the apartment because the landlord was so nice.”

The team helped him do the cleaning and then took him to hospice, where he died a peaceful death.

“Most of our folks think they will die alone, that their future is canceled,” Feldman says. “Bringing hope is more important than any medicine.”