Two of the ten deadliest killings were known to involve shooters with mental disorders. It was suspected in a third.

(3-5-18) The mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida was horrific and also different for me.

After the shootings at Virginia Tech, in Tucson, Aurora, Newtown and the Washington Navy Yard, I penned Op Eds and did radio/ television interviews during which I spoke about how waiting for someone to become dangerous was foolish and the inadequacies of our current mental health care system.

Editors and reporters were eager to print and broadcast my comments.

This time I tried a different tactic. Armed with a 2016 study, Mass Shootings and Mental Illness by James L. Knoll IV, M.D. George D. Annas, M.D., I explained that Americans with serious mental illnesses were not responsible for a majority of mass murders and, in fact, were much more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators.

This is what nearly every advocate is expected to say. Perhaps that is why none of the media outlets, with whom I regularly deal, expressed much interest in my argument. (A person is about 15 times more likely to be struck by lightning in a given year than to be killed by a stranger with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or chronic psychosis.)

With the exception of journalist Tim Williams who interviewed me for NewsTalk Florida, I don’t think any of the others believed me.

A Washington Post/ABC poll found – as Slate put it in its headline – “More Americans Blame Mass Shootings on Mental Health Than on Gun Laws.”

“77 percent, said better mental health monitoring and treatment would have averted Parkland.”

This is the prevailing attitude even though repeated studies prove otherwise. Why?

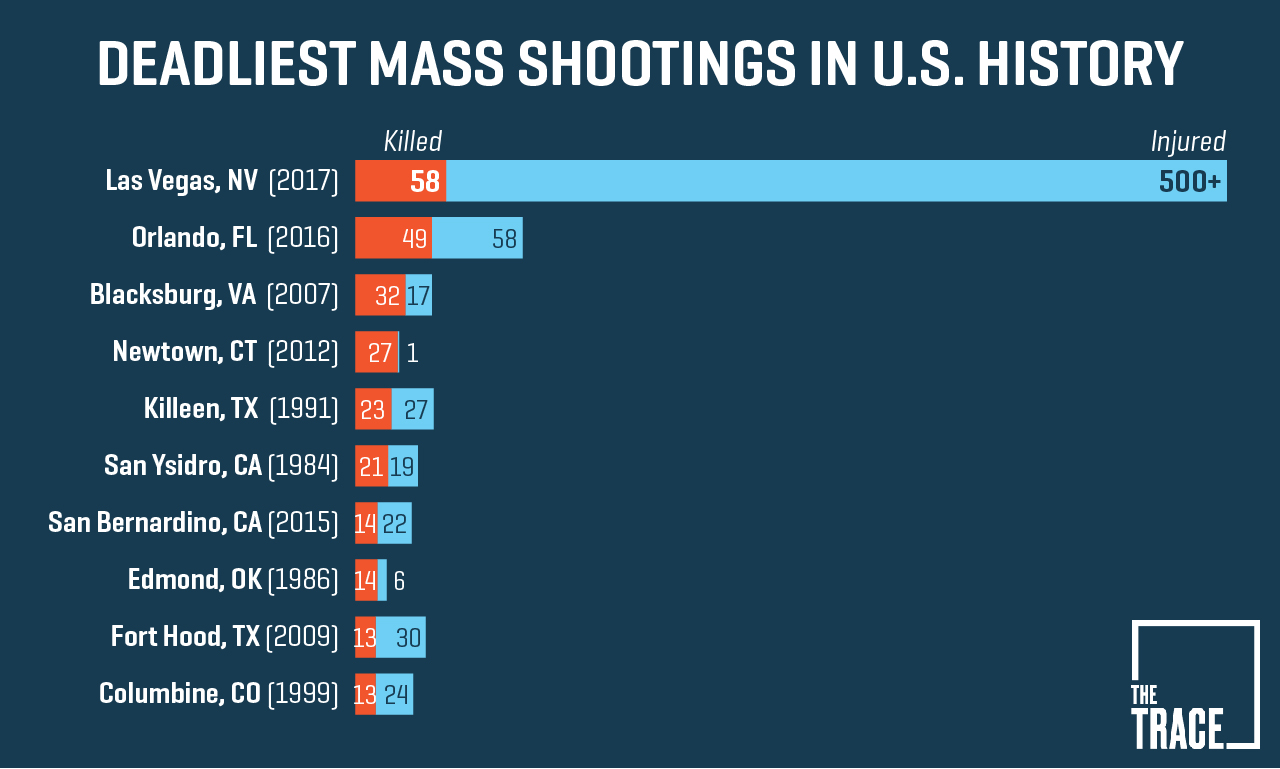

According to the 2016 report (cited above) shootings by gunman (yes, these mass murders are statistically always done by men) with a diagnosed mental illness have received much more media attention. Take another glance at the graph above. Which of these killings stick out in your memory?

Add to this the commonly recited assumption that only someone who is “crazy” would commit mass murder.

There is also another deeply rooted link.

Before nearly all mass shootings committed by someone with a known, diagnosed mental illness there were warning signs. (Think Virginia Tech and Tucson.) People around the shooters knew something was wrong.

This suggests these killings could have been prevented.

If only we changed involuntary commitment laws so someone could have intervened before Stage Four of the illness took control. That would end mass murders. If only legislators passed tougher laws to keep firearms out of the hands of “dangerous persons” – the new code word for Americans with mental illnesses. That would end mass murders.

“Part of the problem is we used to have mental institutions … where you take a sicko like this guy,” President Trump said in a discussion with state and local officials. “We’re going to be talking seriously about opening mental-health institutions again.”

Americans with serious mental illnesses always have been easy targets. Blaming them for mass shootings provides simple solutions and simple solutions make the public feel safer even if they are not fact based. (Read the 2016 report or the editorial at end of this blog.)

Which brings me back to Parkland – and a short tale written by Danish author Hans Christian Andersen, about the Emperor who wore no clothes. Two weavers promise an emperor a new suit of clothing unlike any other. They present him with an “invisible” outfit and explain only those who are stupid or incompetent cannot see it. In that well-known story, it is a child watching the emperor parade naked down the avenue who finally cries out, “But he isn’t wearing anything at all!”

Students at Parkland have correctly cried out that these killing are happening because it is too easy to access military style assault weapons. And it is their pleas that have been the most effective at focusing the national debate where it should be.

Editorial

A Reassessment of Blaming Mass Shootings on Mental Illness

Several recent mass shootings in the United States have prompted calls to address untreated serious mental illness.

This rhetoric—delivered by policy makers, journalists, and the public—focuses the blame for mass shootings on individuals with serious mental illness (specifically, schizophrenia and psychotic spectrum disorders, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder), with less attention paid to other contributory factors, such as access to firearms.1

Furthermore, attributing mass shootings to untreated serious mental illness stigmatizes an already vulnerable and marginalized population, fails to identify individuals at the highest risk for committing violence with firearms, and distracts public attention from policy changes that are most likely to reduce the risk of gun violence.

Serious Mental Illness as a Marker for Violence

Serious mental illness is associated with a marginally higher risk of violent interpersonal behavior. For instance, compared with the general population, individuals with first-onset psychosis may have a 3 to 5 times higher risk of violence.2 However, this and similar estimates are derived from studies with varying definitions of aggression (ranging from verbal threats to physical assaults) and different comparison groups. Furthermore, these relative risks obscure the low absolute risk of violence among individuals with serious mental illness; estimates suggest that only about 4% of criminal violence can be attributed to individuals with mental illness.2 In addition, individuals with serious mental illness are 3 times more likely to experience violence than perpetrate violence, and the violence perpetrated by individuals with serious mental illness is rarely lethal.2

These data suggest that most individuals with serious mental illness will not engage in interpersonal violence, much less mass shootings, and therefore, a diagnosis of a serious mental illness is not a specific indicator for risk of acts of violence.3

In regard to the specific association between serious mental illness and gun violence, 1-year follow-up data from the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study (4) revealed that only 23 of 951 individuals (2.4%) who had been released from an inpatient psychiatric setting engaged in gun violence; 21 of those who engaged in gun violence (91.3%) had a pre-hospitalization history of arrests.

Furthermore, individuals with serious mental illnesses constitute the minority of convicted violent gun offenders; for instance, only 104 of 838 adults (12.4%) charged with violent gun offenses in state prisons had a history of psychiatric hospitalization.5

Although many individuals with serious mental illness have no history of psychiatric hospitalization, these results provide compelling evidence that gun violence cannot be attributed to mental illness alone. In addition, these and similar data point to at least 2 conclusions. First, a diagnosis of serious mental illness does not provide a sensitive estimate of future interpersonal violence (gun-related or not).

Second, laws that limit gun ownership based on a history of involuntary psychiatric commitment, for instance, will still miss most individuals at high risk for gun- related violence and suicide.3

Factors Other Than Serious Mental Illness Diagnosis That Contribute to Violence Risk

Among the multiple individual characteristics that contribute to the risk of gun violence, diagnosis of a serious mental illness is only one. Other static risk factors include male sex; younger age; a history of prior violent acts or experiencing violence; convictions for violent offenses, unlawful use of firearms, or possession or distribution of narcotics; and gang affiliation.6

In addition, multiple dynamic factors are strongly associated with the risk of violence among individuals with serious mental illness, such as substance or alcohol intoxication, treatment non-adherence, and psychosocial stressors (eg, housing instability).2

Looking beyond individual risk factors, relatively liberal firearm access in the United States is a significant contributor to gun violence. For instance, states with higher gun ownership have higher rates of gun-related homicides.7

Even those with prior inpatient psychiatric hospitalization who may be banned in certain states from purchasing firearms report accessing guns from sources not subject to federal regulation (eg, family or friends); in the aforementioned study of violent gun offenders in state prisons,5 78% of those who had a history of psychiatric hospitalization obtained guns from these non- regulated sources.

The Harm of Blaming Mass Shootings on Serious Mental Illness

Given that a diagnosis of a serious mental illness accounts for, at most, only a small proportion of interpersonal violence and that most individuals with serious mental illness will not commit an act of violence (much less a mass shooting), directing public attention to mental illness as the primary cause of gun violence only serves to reinforce negative public attitudes about this population.3

Many individuals with serious mental illness face shame, societal rejection, stigmatization, and challenges associated with stable employment and housing. Genuine efforts to reduce untreated serious mental illness would include addressing systemic factors, such as fragmentation of mental health care, lack of men- tal health insurance coverage, and disparities in coverage for mental health conditions; shortages and uneven geographic distribution of the mental health workforce; socioeconomic factors such as poverty; and treatment nonadherence.

We need to improve the treatment of individuals with serious mental illness not because they are the perpetrators of violence but rather because they need access to treatment to improve their quality of life. By reinforcing stigma against individuals with mental illness, these individuals may be less likely to seek treatment for their mental health problems, thus increasing the risk of suicide and other sequelae of untreated mental illness.1,2

The Need for a Multipronged Approach

Attributing mass shootings to untreated, serious mental illness is politically expedient; by drawing attention to those with serious mental illness, policy makers may avoid having to make difficult decisions about regulating firearm distribution and access.

A more nuanced approach to reducing gun violence would address the many other behavioral characteristics associated with interpersonal violence, the association between rates of gun ownership and gun-related violence, and universal screening protocols for firearm access in clinical settings. The risk of violence is not static; situational factors such as intoxication or recent episodes of domestic violence are associated with increased rates of aggressive acts.3 Several states have incorporated these factors into their gun-control laws; for instance, California’s Gun Violence Restraining Order allows family members to petition to temporarily remove firearms from an individual who poses a clear danger to the public or to himself or herself during a psychiatric crisis. Likewise, gun restriction legislation should include a standardized process by which to restore gun access rights to individuals after a high-risk period (eg, a sustained period of sobriety or resolution of an episode of domestic violence).

As a society, we have a responsibility to reject reductionist explanations for mass shootings. The burden of untreated serious mental illness is expressed more often in human problems, not in acts of violence.

Addressing the risk of future mass shootings requires addressing a wide range of individual, community-level, and national and state policy factors, including decreasing access to guns, especially during periods of heightened violence risk. Likewise, identifying and assisting those with serious mental illness requires the investment of resources and coordination of services, including supportive case managers, law enforcement and emergency personnel, and mental health clinicians. Reducing the risk of mass shootings and improving mental health care are 2 different issues and should not be conflated.

Millions of Americans who are diagnosed with serious mental illness will never engage in any gun violence and should not be further stigmatized.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

1. McGintyEE, WebsterDW,JarlenskiM,BarryCL. News media framing of serious mental illness and gun violence in the United States, 1997-2012.

Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):406-413.

2. RozelJS, Mulvey EP.The link between mental illness and firearm violence: implications for social policy and clinical practice. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2017;13:445-469.

3. SwansonJW,McGintyEE,FazelS,MaysVM. Mental illness and reduction of gun violence and suicide: bringing epidemiologic research to policy. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(5):366-376.

4. SteadmanHJ,MonahanJ,PinalsDA,Vesselinov R, Robbins PC. Gun violence and victimization of strangers by persons with a mental illness: data from the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(11):1238-1241.

5. KivistoAJ.Gun violence following inpatient psychiatric treatment: offense characteristics, sources of guns, and number of victims. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(10):1025-1031.

6. MetzlJM,MacLeishKT.Mental illness,mass shootings, and the politics of American firearms. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):240-249.

7. SiegelM,RossCS,KingCIII.The relationship between gun ownership and firearm homicide rates in the United States, 1981-2010. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(11):2098-2105.