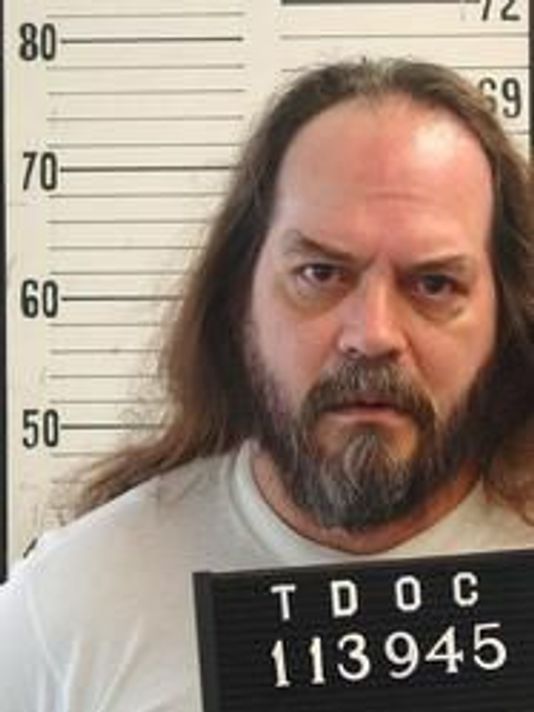

(8-6-18) Tennessee is scheduled to execute Billy Ray Irick in three days even though he has a long, well documented history of mental illness – a fact jurors were never told during his 1986 trial. Incorrectly, they were specifically advised that he was not mentally ill.

In addition, Irick has the mental cognitive acuity of someone who is seven to nine years old. He is fifty-nine.

The National Alliance on Mental Illness, NAMI Tennessee and a state coalition – created specifically to oppose the killing of Tennessee inmates with severe mental illnesses – are urging the public to contact Tennessee Governor Bill Haslam at bill.haslam@tn.gov or by calling his office at (615) 741-2001. They are asking Haslam to commute Irick’s death sentence to life in prison without any possibly of parole. Irick has spent the last 30 years on death row. The governor’s commutation is considered his last chance.

In their letter to the governor, NAMI CEO Mary Giliberti and NAMI Tennessee Executive Director Jeff Fladen stated:

“Powerful delusions or hallucinations characteristic of psychosis may lead a person to act in ways they never would have otherwise…”

They argue two critical points:

- Executing Billy Ray Irick would run contrary to constitutional restrictions on imposing capital punishment on persons with diminished capacity due to mental disabilities.

- Information about Billy Ray Irick’s severe mental illness and its impact was never properly considered at his trial or his sentencing.

Tennessee Attorney General Herbert Slatery is pushing back, insisting the state has a right to “execute its moral judgment” and put Irick to death.

Irick’s crime was horrific. All death row convictions are. He raped and murdered Paula Dyer, a seven year old girl, he was babysitting.

The first mistake

During the trial, jurors were specifically told that Irick was not mentally ill. This was based on a single psychologist questioning him in jail – an interview that lasted less than an hour and didn’t include any detailed investigation into his past. It was only after Irick was sentenced to death that a new team of mitigation attorneys fully explored his childhood. Based on their probe, eight mental health professionals, some hired by the state and others by the defense, all agreed that Irick was and remains seriously mentally ill.

In addition, the psychologist, who originally testified that Irick was not mentally ill, flip-flopped and notified the court that after reviewing the new evidence, he was now confident that Irick was severely impaired when the crime happened.

Courts frequently refuse to allow new evidence to be admitted after a death sentence has been imposed. A thorough background check into Irick’s past should have happened when he was arrested.

Warning Signs That Went Unheeded

Those of you who want to read testimony about Irick’s past can find it here. For brevity, here’s a short-hand version by STEVEN HALE, published in Nashville Scene.

Billy Ray Irick was just 6 years old the first time someone raised questions about his mental health. It was March 1965, when he was in the first grade. His school’s principal referred him to the Knoxville Mental Health Center, requesting a mental evaluation to determine, according to court documents, “whether Billy’s extreme behavioral problems and unmanageability in school were the result of emotional problems or whether Billy suffered from some form of ‘organic brain damage.’ ”

A clinical social worker at the center performed an assessment, noting that the young boy “apparently mistreats animals” and that he had “for a couple of years been telling people outside the home that his mother mistreats him, that she ties him up with a rope and beats him.”

Later, a psychologist at the center who interviewed Irick concluded that he was most likely “suffering from a severe neurotic anxiety reaction with a possibility of mild organic brain damage.” The young boy, the psychologist noted, tended “to fear his own impulses.”

Nearly seven years after those evaluations, a then-13-year-old Irick was living at the Church of God Home for Children in Sevierville, Tenn. — a former orphanage that provided care for abused and emotionally disturbed children. His parents, whose mental and emotional stability had also been questioned, rarely visited him between the ages of 8 and 13. But in June 1972, according to testimony included in court documents, the facility arranged for Irick to visit his parents at home.

According to court documents, the visit did not go well: “During the visit, Billy used an axe to destroy the family television set, clubbed flowers in the flower bed, and, in a very disturbing incident, used a razor to cut up the pajamas that his younger sister was wearing as she slept. The razor was later found in his sister’s bed.”

So here we have a deeply troubled boy.

The second investigation concluded that Irick was an unwanted child, left in an orphanage because there were no mental health hospitals for children at the time. He was given Thorazine at age six. At age thirteen, as cited above, he was sent home for a visit and found hovering over his sister’s bed with a razor.

What happened next?

Irick was returned to the orphanage where he was later spotted standing over a sleeping girl’s bed with a knife in his hand. He ran away.

Two Terrifying Incidents – Yet No Treatment

When he turned fourteen, Irick was sent home. There was no treatment plan. No outpatient care. Instead, he returned to a house where he was physically and emotionally abused, according to court records.

When he turned eighteen, he joined the Army. Little is known about what happened during this period or the two years after he left the service and wandered across the country. A throw-away child, he remained a throw-away member of society.

A childhood friend, Kenneth Jeffers, invited Irick to live with him and his parents, Ramsey and Linda Jeffers. His friend was divorced but still had his daughter, Paula Dyer, living with him on occasion. In return for staying with the Jeffers, Irick was asked to babysit and care for the children in the house.

Back to Reporter Hale’s account:

In 1999 …an investigator traveled to Knoxville to speak to potential witnesses. Surprisingly, the investigator discovered that no one had interviewed members of Paula Dyer’s stepfamily, with whom Irick had been living in the weeks before her murder. The investigator learned that “just days or weeks before Paula Dyer’s death,” Irick, wielding a machete, had chased a school-age girl down a Knoxville public street in broad daylight “with the explanation that he ‘didn’t like her looks.’ ”

Ramsey and Linda Jeffers — the parents of Dyer’s stepfather, Kenny Jeffers — and their daughter Cathy signed affidavits attesting that Irick had been “talking with the devil,” “hearing voices” and “taking instructions from the devil.”

Cathy Jeffers, the court document says, testified that Irick had told her “the only person that tells me what to do is the voice” and that on one evening, as paraphrased in the court filing, he’d been “frantic that the police would enter the home and kill them with chainsaws.”

After reviewing the Jefferses’ affidavits, Dr. Clifton Tennison — the psychologist who performed the initial mental health examination before Irick’s original trial — stated in an affidavit that he no longer had confidence in his initial evaluation, which had been used to argue against an insanity defense.

“The information contained within the attached affidavits raises a serious and troubling issue of whether Mr. Irick was psychotic on the date of the offense and at any previous and subsequent time,” he wrote.

Two more psychologists reviewed the affidavits and other records related to Irick’s mental health and concluded that he “suffered at the very least from a dissociative disorder, and probably was schizophrenic or intermittently psychotic.”

In a brief filed in 2010, Irick’s attorneys argued that he “was experiencing a psychotic episode with hallucinations and/or delusions and that he has no memory of the offenses themselves or his role in them.”

Further, they contended that Irick did not, and could not, “have a rational understanding of his pending execution because he has no memory of the offenses, does not believe that he committed them, and has the emotional and social functioning of a child.”

Their efforts were blocked on procedural grounds, and the state Supreme Court affirmed the trial court’s judgment that Irick was “competent to be executed.”

Should his mental illness matter – legally?

In an Intercept article about the Irick case, Liliana Segura explained the legal precedents.

In 1986, the same year Irick went to death row, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down Ford v. Wainwright, involving a condemned Florida man with paranoid schizophrenia. The ruling barred the execution of the “insane” on 8th Amendment grounds, but left it up to the states to determine who was “competent” to be executed.

In 2007, in the case of Scott Panetti, diagnosed as paranoid schizophrenic, the U.S. Supreme Court reaffirmed the Ford decision, ruling that condemned people must have a rational understanding of why a state intends to execute them.

But this has done little to prevent states from killing people with serious mental illness, including those who were suffering symptoms at the time of their crimes.

Last year, Virginia executed 35-year-old William Morva for the murder of two police officers, despite significant evidence that the killings were driven by delusions.

I have written previously about both Panetti and Morva. I chastised Democratic Gov. Terry McAuliffe’s for his pusillanimous behavior when he refused – apparently for his own future political gain – to stop Morva’s July 6, 2017 execution.

I have been opposed to the death penalty since writing my book, CIRCUMSTANTIAL EVIDENCE, which chronicles a death penalty case. I am especially opposed to executing individuals with severe mental illnesses who have limited mental capacity, such as Irick.

What he did was ghastly. That’s why his attorneys are not trying to free him. He will spend the rest of his life behind bars. Executing him will only add another inhuman act to what already has happened. He will not be released from prison if Gov. Haslam commutes his sentence. He will not pose a danger to society.

I will be joining NAMI today in contacting the governor. I hope you will too.

NAMI Letter Requesting Clemency: Stay Of Execution

August 1, 2018

The Honorable Bill Haslam Governor of Tennessee

1st Floor, State Capitol, Nashville, TN 37243Dear Governor Haslam,

We are writing on behalf of the national office of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) and NAMI Tennessee, to respectfully request that you commute Billy Ray Irick’s death sentence to life in prison due to his long term severe mental illness. NAMI is the nation’s largest grassroots mental health organization dedicated to building better lives for the millions of Americans affected by mental illness. NAMI Tennessee is NAMI’s state organization in Tennessee and the largest grassroots organization focused on mental health conditions in the state, with 23 local affiliates throughout the state.

As Chief Executive Officer of NAMI and Executive Director of NAMI Tennessee respectively, we are all too aware of the harmful impact that false, negative stereotypes associating mental illness with violence can have on societal perceptions. However, we are also aware that a small number of people may engage in acts of violence due to the symptoms of their severe illnesses. In some cases, such as Billy Ray Irick’s case, powerful delusions or hallucinations characteristic of psychosis may lead a person to act in ways they never would have otherwise.

Societal lack of understanding about mental illness is one of the reasons NAMI supports an exemption to the death penalty for people with severe mental illness. People with these conditions are more likely to be sentenced to death than those without mental illness due to false perceptions that these individuals are inherently violent and beyond redemption. We also know that jurors are frequently presented with inaccurate information about defendants with severe mental illness, reinforcing perceptions that the crimes were products of willful choices rather than the severe, untreated symptoms of their mental illness.

NAMI and NAMI-Tennessee request that the execution of Billy Ray Irick be commuted to life without parole for the following reasons.

• Executing Billy Ray Irick would run contrary to constitutional restrictions on imposing capital punishment on persons with diminished capacity due to mental disabilities.

Mr. Irick’s severe mental illness was first detected at the age of 6, when he was referred for mental health treatment by teachers and administrators at the school he was attending due to his erratic and disturbing behaviors. At age 8, he was committed to the Eastern State Psychiatric Hospital due to his severe psychiatric symptoms where he remained for 10 months. His serious and sometimes disruptive psychiatric symptoms continued throughout his adolescence and into early adulthood.

In 1999, 13 years after his trial, conviction and sentence of death, investigators working on an appeal interviewed the step family of the girl who was murdered and with whom Irick had been living with at the time of the crime. They signed affidavits stating that Irick was very paranoid, hallucinating, hearing voices, and “talking with the devil” during this period.

From all reports, Irick’s severe mental illness has continued unabated during his many years of incarceration. The fact that eight experts, working for both the state and the defense, agree that he suffers from severe mental illness is powerful evidence in support of this point.

The U.S. Supreme Court, in banning the execution of people with intellectual disabilities and juveniles, has clearly stated that it is cruel and unusual to impose the ultimate penalty of death on people whose brains may not be fully developed or are impaired in some way or another.i The Court has further clarified that the death penalty cannot be carried out on individuals whose mental illness or disability impairs their capacity to rationally understand the nature of the crimes committed or the reasons why the death penalty is being carried out.ii

The criminal code of Tennessee emphasizes that the death penalty, when carried out, should be limited to cases in which aggravating factors clearly outweigh mitigating factors. And, severe mental illness is included under two of the factors listed in Title 39, Ch. 3, Part 2, Sect. 39-D-204 in mitigation against the death penalty.

(j)(2): “The murder was committed while the defendant was under the influence of extreme mental or emotional disturbance;”

(j)(8): “The capacity of the defendant to appreciate the wrongfulness of the defendant’s conduct or to conform the defendant’s conduct to the requirements of the law was substantially impaired as a result of mental disease or defect or intoxication, which was insufficient to establish a defense to the crime but which substantially affected the defendant’s judgment.”

• Information about Billy Ray Irick’s severe mental illness and its impact was never properly considered at his trial or his sentencing.

At trial, the State’s psychiatric expert testified that he did not believe there was any evidence of mental illness. He based this conclusion on a one-hour interview he conducted with Irick. However, when presented with the new evidence uncovered by the investigator in 1999, he recanted his findings and stated that “in light of this new evidence, my previous evaluation and the resulting opinion were incomplete and therefore not accurate.” He further stated that “without further testing and evaluation, no confidence should be placed in Mr. Irick’s 1985 evaluations of competency to stand trial and mental condition at the time of defense.”

When this information was presented to the District Court, the Court determined that it could not consider the merits of this new evidence due to a technicality. “Therefore, accurate information concerning Irick’s mental state at the time of the crime was not presented at trial or sentencing, nor has it ever been heard of considered by any Court.” (emphasis added). It is clear that the process of fairly evaluating the impact of mental illness as a mitigating factor did not occur.

Governor Haslam, in view of these factors which raise serious concerns about the impact of Billy Ray Irick’s severe mental illness on his actions at the time of his crime, NAMI and NAMI- Tennessee respectfully request that you step in and stop his execution. While we in no way wish to excuse the severity or impact of his crime, we believe that executing Mr. Irick on August 9th will only compound the original tragedy, represent a profound injustice, and serve as neither retribution nor deterrence. We therefore implore you to commute his death sentence to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole.

Thank you for your careful attention to this letter. Sincerely,

Mary T. Giliberti, J.D., Chief Executive Officer

NAMI Tennessee

Jeff Fladen, Executive Director NAMI