Photos by Pete Earley

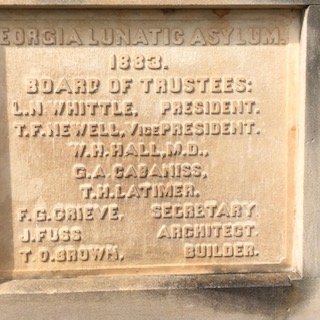

(3-15-19) I recently spoke at a nursing symposium at Georgia College in Milledgeville. I took advantage of my trip to visit Central State Hospital on the edge of that community. During the 1960s, it was the largest state mental hospital in the world with more than 12,000 residents.

It is difficult to walk its largely deserted grounds and read its history without feeling an abiding sadness. While there were periodic efforts to treat patients humanely, the hospital never received sufficient state funding or had adequate staff to care for those confined there. Nor did its doctors know how to help most patients. Thousands died and were buried in unmarked graves. The state announced it would close the hospital in 2010, but instead now uses parts of it to house forensic patients.

The asylums are nearly gone, replaced by jails and prisons. Is this progress?

MILLEDGEVILLE — The first patient came to Georgia’s first insane asylum on Dec. 15, 1842, chained to a horse-drawn wagon. Tilman Barnett, described as violent and destructive, diagnosed as a “lunatic, ” never left. Barnett, a 30-year-old farmer from Bibb County, died six months later of a malady termed “maniacal exhaustion.” –Alan Judd, writing in The Atlanta News

Patients were admitted for “intemperance, ” “religious excitement, ” “domestic unhappiness, ” “ill health and jealousy.” One early patient was described as “rather idiotic.”Of the first 50 patients, 29 died without ever leaving. Records list causes of death as dysentery, chronic diarrhea, convulsions, and “general paralysis.”Just eight of the first 50 were pronounced “cured.”

“When we were growing up in Georgia, they used to say, ‘If you don’t behave, we’ll send you to Milledgeville, ‘ ” Fricks said recently. “Everyone knew what that meant. … That was like a death sentence.” –Alan Judd, Atlanta News

That history played out in a seemingly endless cycle: good intentions, not enough money, poor psychiatric and medical treatment, too many patients with too few caretakers, abuse and neglect, expose and scandal, and, eventually, high-minded but fleeting reforms.

Outdoor solitary, windowless boxes for confining troublesome patients.

In 1959, the Atlanta Constitution’s Jack Nelson investigated reports of a “snake pit.” Nelson found that the thousands of patients were served by only 48 doctors, none a psychiatrist. Indeed, some of the “doctors” had been hired off the mental wards. Yes, the patients were helping to run the asylum. The series rocked the state. Asylum staff were fired, and Nelson won a Pulitzer.

The state, which had ignored decades of pleas from hospital superintendents, began to provide additional funding. By the mid-1960s, as new psychiatric drugs allowed patients to move to less restrictive settings, Central State’s population began its steady decline. A decade before the national movement toward deinstitutionalization, Georgia governors Carl Sanders and Jimmy Carter began emptying Central State in earnest, sending mental patients to regional hospitals and community clinics, and people with developmental disabilities to small group homes. Doug Monroe, Atlantic Magazine

Thousands of Georgians were shipped to Milledgeville, often with unspecified conditions, or disabilities that did not warrant a classification of mental illness, with little more of a label than “funny.” The hospital outgrew its resources; by the 1950s, the staff-to-patient ratio was a miserable one to 100. Doctors wielded the psychiatric tools of the times—lobotomies, insulin shock, and early electroshock therapy—along with far less sophisticated techniques: Children were confined to metal cages; adults were forced to take steam baths and cold showers, confined in straitjackets, and treated with douches or “nauseants.” “It has witnessed the heights of man’s humanity and the depths of his degradation,” Dr. Peter G. Cranford, the chief clinical psychologist at the hospital in 1952, wrote in his book, But for the Grace of God: The Inside Story of the World’s Largest Insane Asylum.

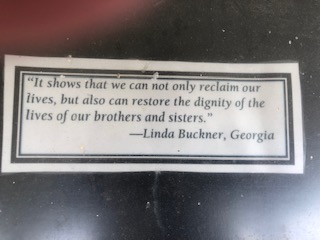

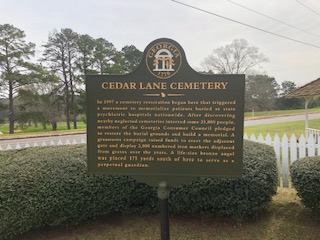

For grounds keepers, the markers amounted to a nuisance when they mowed the cemeteries. In the late 1960s, they simply pulled stakes from the ground — at least 10,000 of them — and tossed them into the woods.Isolated in life, each grave’s occupant would be forever anonymous in death. (This was before the Georgia Consumer Counsel restored the cemetery.)

Metal stakes added by Georgia Consumer Counsel to memorialize more than 10,000 patients who were buried and forgotten.