(Note: My blog announcing Silverstein’s death prompted complaints by some readers who said I was overly sympathetic. I responded by posting a second blog about their criticism.)

(5-12-19) Thomas Silverstein, a major character in my bestselling book, The Hot House: Life Inside Leavenworth Prison, and one of America’s most famous federal prisoners, has died.

He died Saturday (5-11) evening in a Colorado hospital from heart complications. He had been hospitalized for several weeks. He was 67.

Silverstein had been held in isolation since 1983, after he killed Corrections Officer Merle Clutts at the Marion Penitentiary in Illinois. At the time, there was no death sentence for murdering a correctional officer. Bureau officials told me, while I was researching my book, that they created a new punishment for Silverstein called “no human contact” designed to completely seal him off from other prisoners and the outside world.

Prison officials explained they had little choice but to isolate Silverstein. By the time he murdered Clutts, Silverstein already had been found guilty of the brutal murders of three other prisoners, although his conviction of one of those murders was later overturned.

Initially, he was held in the bureau’s Atlanta maximum security penitentiary with absolutely nothing in his cell with the lights on 24 hours per day. He later was moved to an isolation cell in the bowels of the federal penitentiary in Leavenworth where I first met him in 1987. The lights were kept on 24 hours per day there too – under the pretense they were needed so that cameras could monitor him. For months he was only provided with freezing cold water for showers. Most of the officials who oversaw him refused to speak to him. He had little idea whether it was day or night, and no idea what was happening in the outside world.

Prison officials gradually began granting Silverstein privileges, such as books and art supplies for his paintings. This was not necessarily done out of kindness, but for practicality. Having something to take way as punishment if he didn’t obey a direct order – such as return a food tray after eating.

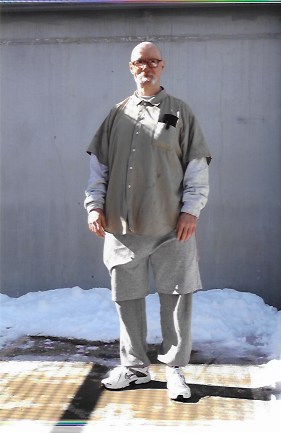

Silverstein spent his last 36 years in isolation – believed to be the longest an American has been held in such conditions by federal officials. He prided himself, in his words, “for not letting them break me!”

He was serving a life sentence in an isolation cell at the federal “Supermax,” the United States Penitentiary, Florence ADX (USP Florence ADX) in Colorado, when he became ill earlier this year and was taken to a Denver hospital for treatment. Even when he was incapacitated and incubated, I was told that his BOP guards initially kept him in four point restraints tied to a hospital bed with as many as three officers standing watch. Hospital officials told callers that there was no patient named Silverstein being treated and get-well cards were returned “undeliverable” apparently to keep his location a secret.

(Before his death, his ex-wife, daughter, and his fiancee – were allowed to see him.)

While other inmates have periodically attacked and killed correctional officers, Silverstein’s actions were responsible for ushering in a new era in modern day corrections.

In the early 1980s, federal prison officials had begun sending the so-called “worst of the worst” prisoners to the penitentiary in Marion, this included gang members. The BOP (federal Bureau of Prisons) identified Silverstein as a member of the Aryan Brotherhood, a notorious and feared white supremacy prison gang, although he never acknowledged being a member. By 1983, Marion had become dangerous for both inmates and those who worked there. The same day that Silverstein murdered Officer Clutts, another inmate, Clayton Fountain (an acknowledged Aryan Brotherhood member) fatally stabbed Correctional Officer Robert Hoffmann. (Fountain died at the United States Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Springfield, Missouri in 2004.) With two officers dead, then-BOP Director Norman Carlson ordered USP Marion to be put on an indefinite lockdown until staff could regain control of the prison. That lockdown led to the BOP practice of keeping its high profile and dangerous prisoners locked in solitary confinement for long periods and ultimately led to the creation of the “Supermax” which opened in 1994. Soon, state prisons began copying the Supermax, leading to widespread use of solitary confinement as punishment.

After I met Silverstein, we began corresponding regularly. He was a year younger than I am and early on, I would frequently think of him as I was experiencing ordinary life events, such as having children, holiday celebrations, graduations, marriages, and the deaths of my parents. Such experiences for him were recounted only through letters and phone calls.

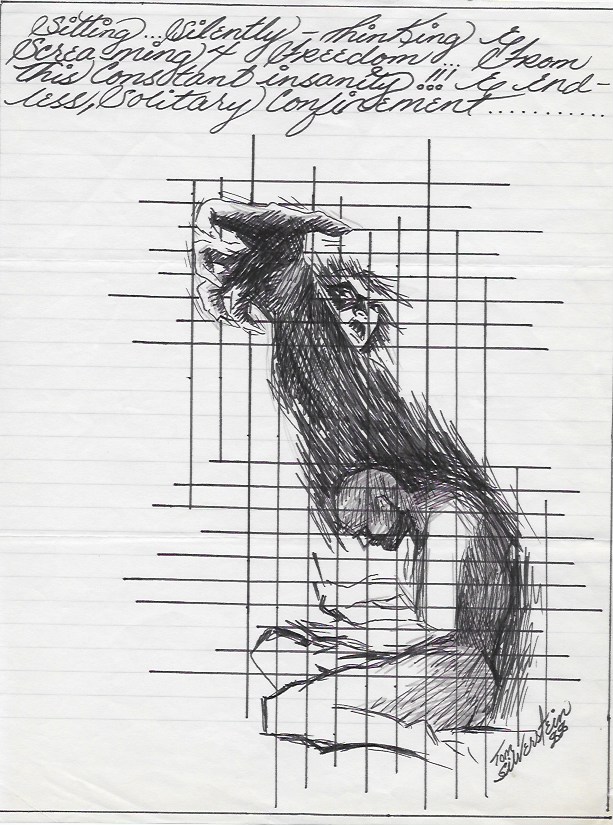

In a drawing that Silverstein did for me, he wrote: “Sitting, silently, thinking, screaming 4 freedom from this constant insanity and endless solitary confinement…” I asked him once what it was like to be in isolation. He suggested that I go into my bathroom, shut the door and not come out for twenty-four hours. I lasted less than an hour.

Despite such isolation, I received a letter from him once, in which, he wrote: “It is two a.m. and I need to get to bed, but I still have a lot to do…”

He occupied himself by painting – becoming a skilled artist. He sent his drawings and artwork to those who corresponded with him. The BOP refused to allow him to show or sell his art. He also practiced meditation and yoga. After my book was published, he became a celebrity, and spent hours writing letters, including to several individuals in foreign countries. Articles about him often glamorized him, much to the dislike of the BOP and the Clutts’ family.

The last time that we spoke about Officer Clutts, Silverstein told me that he deeply regretted killing the veteran officer. It wasn’t because he felt sympathy for Clutts or sorrow for murdering him. He insisted that Clutts had “tortured” him by destroying his artwork, tampering with his food, and not delivering his mail, rather he regretted his actions because, in his words, “killing him cost me my life too.”

He told me that he frequently had nightmares about killing the officer.

His letters were filled with contempt toward the BOP and the criminal justice system. He frequently reminded me that since Clutts’ murder, he had become a “model” convict, with no major infractions, but none of that mattered in how he was being treated. At one point during riots in Atlanta, he had an opportunity to take revenge against BOP officers being held as hostages. He chose not too and was bitter when he later learned that federal officials had been given permission to “shoot on sight” if they encountered him while regaining control of the penitentiary. (In the end, it as a group of prisoners who overpowered him and turned him over to federal law enforcement.)

I spent a year at Leavenworth between 1987-89 and during my research I saw first-hand how Silverstein had become a mythical figure. Most correctional officers had never met him, yet they considered him the devil incarnate. (He claimed to me that every new warden put in charge of him, immediately stripped him of his privileges to show he didn’t believe in coddling him.) Meanwhile, convicts, most of whom had never met him, spoke of him as if he were a convict super hero.

In truth, he was neither.

I have always condemned his decision to take Clutts’ life in writing and in our conversations. Nor did I agree with his political and world views. But during the 32 years that Tom Silverstein and I corresponded and spoke on the phone, we developed an unusual friendship and respect for one another. He helped me better understand the insular prison world that he lived in. He was also one of the strongest persons mentally whom I’ve met. I will remember his resilience, how differently we saw the world because of our circumstances, and his sense of humor despite his being in isolation.

I once asked him in my best Barbara Walters/Oprah Winfrey probing manner how he managed to sleep with the lights turned on twenty-four hours per day.

“Pete,” he said, “I shut my eyes.”

Until he became sick, he believed that someday he would be free.

He finally got his wish.