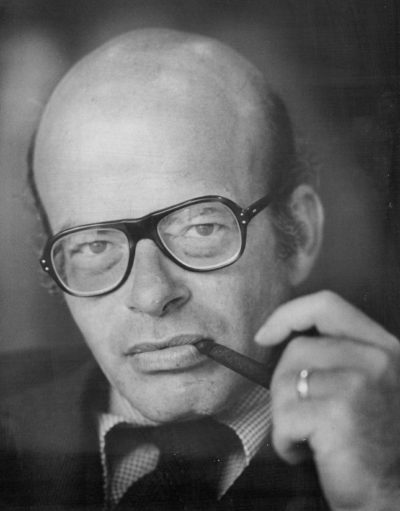

(11-18-19) In 1973, Dr. David L. Rosenhan, a professor of psychology at Stanford University, announced that he and seven others had pretended to have a serious mental illnesses and were subsequently hospitalized and diagnosed with schizophrenia even though they were faking.

His report, On Being Sane In Insane Places, published in Science, the journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, shocked the country and deeply weakened the public’s faith in psychiatrists, state mental hospitals, and psychiatry itself.

The article has been embraced for decades by the anti-psychiatry movement as proof mental illnesses are a “social construct” and do not exist. His study “plunged the field into a crisis from which it has still not fully recovered,” the New York Times recently noted. “It made Rosenhan an academic celebrity. Nearly 50 years later, it remains one of the most cited papers in social science.”

Dr. Rosenhan, who died in 2012, claimed that three psychologists, a pediatrician, a psychiatrist, a painter and a housewife, joined him in posing as patients. None of the other pseudo-patients was identified in his article, which he intended to publish as a book, nor were the doctors and hospitals that were bamboozled named.

It now appears his study might have been a hoax.

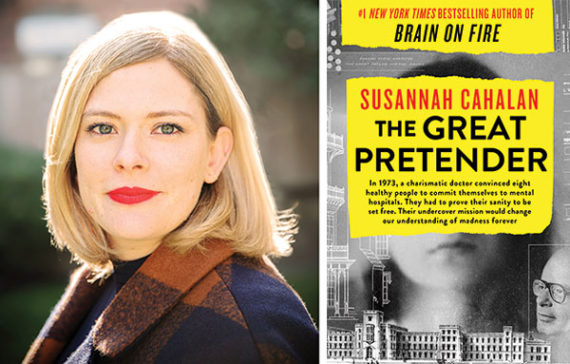

Susannah Cahalan, a former investigative reporter and author of the 2012 best-selling book “Brain on Fire,” is responsible for raising red flags about Rosenhan’s work.

Ten years ago, Cahalan was misdiagnosed as being mentally ill – and that led to her curiosity about Rosenhan.

Dr. David Rosenhan’s study made him an academic celebrity. Was it fake?

When she became ill, Cahalan “believed an army of bedbugs had invaded her apartment. She believed her father had tried to abduct her and kill his wife, her stepmother. She believed she could age people using just her mind. She couldn’t eat or sleep. She spoke in gibberish and slipped into a catatonic state,” according to New York Times writer Emily Eakin.

Instead, doctors discovered Cahalan had “a rare- or at least newly discovered — neurological disease: anti-NMDA-receptor autoimmune encephalitis. In plain English, Cahalan’s body was attacking her brain. She was only the 217th person in the world to be diagnosed with the disorder and among the first to receive the concoction of steroids, immunoglobulin infusions and plasmapheresis she credits for her recovery,” Eakin noted.

In her new book, The Great Pretender, which was released earlier this month, Cahalan dissects Rosenhan’s research in painstaking detail. You can read Eakin’s book review and expose of Rosenhan’s study here.

Put simply, it appears Rosenhan pretty much fictionalized his research. Cahalan began feeling queasy about Rosenhan’s study after she studied his private notes and poured over a 200-page manuscript he was supposed to write for Doubleday but never delivered. Midway through her research, she concluded: “It was becoming alarmingly clear that the facts were distorted intentionally — by Rosenhan himself.”

As noted in the Times review, Rosenhan’s study is not the only influential social science experiment whose validity is being questioned.

Rosenhan’s Stanford colleague Philip Zimbardo, the author of the famous “prison experiment,” in which a simulation involving students posing as “guards” and “inmates” spun violently out of control, was recently found to have coached the “guards” to behave more aggressively — tainting the study’s conclusions about prison’s inherent evil.

Sadly, both studies have had profound influence. Rosenhan’s undermined psychiatry and Zimbardo’s identified institutions as being evil by their nature.

There is no blood test for schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. We still don’t know what causes mental illnesses despite endless genetic and environmental studies. Instead, we must rely on doctors asking patients to describe their symptoms. Rosenhan used this lack of scientific knowledge to spread what now appears to have been, at best, an unsubstantiated theory, and at worse, a lie, to the detriment of us all.

“The more access I got to psychiatry,” said Susanna Cahalan, who wrote “The Great Pretender” after her best-selling memoir “Brain on Fire,” ”the more I realized that I was a marvel and that the average person isn’t and won’t necessarily get the outcome that I did.”Credit…Celeste Sloman for The New York Times