Marie’s wrist strapped to hospital bed after suicide attempt

(1-9-20) In Part One of The Shape of Loss: Teen Suicide and the Failure of Mental Health In Public Schools posted yesterday, the mother of a teenager described the attempts that she made to help her adopted daughter, Marie, before she attempted suicide in December 2019. Both mother and daughter agreed to share their story but pseudonyms are being used to protect the family’s privacy.

The Shape of Loss: Teen Suicide and the Failure of Mental Health in Public Schools: Part Two

Just before starting high school, Marie spent the summer living with her father, my ex-husband, holed up in a dark room, easily weakened from a walk in the woods or around the track. She complained of depression, isolation, a vulnerability that spoke of clipped wings, and I saw a new gauntness around her eyes when she returned home.

During a trip to the Oregon shore, which she loved, I noticed when she pushed up the bottoms of her pants to wade into the ocean, her calves were marked with razor thin white scars that turned shades of pink and purple in the cold water.

A Fresh Start

I spoke of high school all summer, building up the advantage of having a fresh start in a new school, and allowed myself a certain ruthlessness in my optimism. As if I found a twenty-dollar bill in an old wallet, I began to hope that high school might be the ticket. Perhaps, I thought, a new school with greater flexibility, a place where she would finally find her tribe.

It didn’t matter if she was still cruel to me, using words like a golf club that hit the heads off of dandelions, precise and swift, regarding my failures as a parent. She could be pleasant to others.

In September, Marie announced to me that she was going to “Go to school and stay all day. Screw you all. I’m going to get my diploma and get the hell out of this weak-ass town and head to art school!” And, to high school she went.

During the second week an incident happened. She had been befriended by an older teen male who didn’t have many friends. I would later discover he had “anger problems.” I was told the young man was on a “safety plan” at the school, which prohibited him from being in certain areas of the school or alone with females. Because Marie was naïve, she didn’t see the red flags until it was too late. At lunchtime, they walked to a local store which served sandwiches and drinks to students. Marie said he assaulted her in the men’s room there.

Marie no longer was able to feel safe at school after the attack.

The school did not have anyone trained to provide the sort of help Marie needed to deal with trauma.

My daughter slipped into periods of dissociation, wild mood swings, irritability, and high-risk behavior she’d never displayed previously. I immediately began searching for a therapist. This was in September 2019. I first contacted a trauma center for children and was told there was a ten-week wait list. I pushed, cajoled, and pleaded with the only therapist at our local mental health center and he finally agreed to let Marie take a tour of the facility to see if she would warm to the idea of an 18-week course of therapy to manage her traumatic experience.

When he met with us, he told her that they were hiring another therapist with a therapy dog and that perhaps the waitlist might open up faster for this new hire. After the tour, I felt we had a foot in the door. I was mistaken. The social worker, who guided us on the tour, had mentioned that I, myself, was a trained therapist. Therefore, Marie had enough “protective factors” available to her in her home without taking the 18-week course. The social worker also reported that Marie didn’t seem interested in therapy because during the tour, she commented that she would like to “move away and become an artist.” I was informed later that if Marie wanted to be seen at the center, she would have to make the request herself – I couldn’t do it for her – at which point she would be added to the waitlist. There would be a minimum ten-week wait.

I was feeling desperate. My daughter needed help. Now! Marie was stating with more frequency that she was depressed, and her rage continued to build with periods of hypomania and impulsivity.

By this time it was October, I began making more calls and was able to get an appointment with a psychiatric resident who asked if she could film Marie during their interview. She told us that she would be periodically stepping out of session to “talk with my supervisor.” This young woman clearly became uncomfortable when Marie began talking about the bathroom assault. While well-intentioned, she appeared to wince when Marie would swear, and then smile at her as if she was apologizing for doing so. She also had a propensity for wringing her hands and taking long pauses.

As we were leaving, Marie informed me that she felt badly for the woman and that she had in fact “chosen the wrong profession.” Marie said she didn’t want to traumatize her and had no intention of returning.

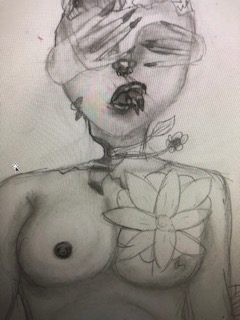

Art Reveals Fractured Images

Marie had been drawing for the past two years, Anime girls with pigtails and freckles. Her drawing took on a different depth, entirely outside of anything she had drawn before. Her mind and spirit were fracturing and scrubbed clean of any hope that “things would get better.

I called every resource in my county that I could, and no one had anything but waitlists or declined our insurance; the therapists with the best potential fit I would email, beg, cajole, and offer to pay out of pocket, not that I could.

Marie was asking for therapy, wanting to try medication again, and there was a desperation I had not seen before: her speech was pressured, she wasn’t sleeping, her irritability and rage made it unsafe for me to be around her. I called my state senator and complained: complained nothing had been done about the assault, complained about no county services or EASA team [EASA teams include counselors, case managers, occupational and supported employment/education specialists, medical staff, and family education and mentorship] – all I heard was there were waitlists.

Our state senator apologized, and agreed, the system was broken.

I spoke in front of a county committee. They gave me five minutes to describe my plight.

“It is interesting that when a child is mentally ill in this community, it isn’t until they commit suicide that resources show up at the school. There is no crisis team for children,” I told them.

The director of the mental health department for our county was present and she did not approach me, did not follow up, or attempt to call, but remained sitting tight-lipped and indifferent.

I continued to make calls demanding action, quoting the civil rights for individuals with mental illness. To strangers I must have appeared strident, my voice like a woman who plants her fists on her hips, wide stanced and angry: and I was.

I could not understand how nothing was being done. A young woman with a mental illness and developmental delay has been assaulted in a men’s bathroom and she couldn’t receive any services?

I described Marie’s response of long periods of staring off in space, restricting food, insomnia, avoiding where it happened, and suddenly high risk behavior all indicative of a trauma response: I explained how teenage girls process assault by a peer differently, and how her depression and processing delay would take time – that this was normal, and that she warranted help and was in no position to “call up disabilities rights of Oregon and the ABC House [ABC House is the child abuse intervention center serving Benton and Linn Counties in Oregon] to request services, “ which was what I was told she had to do.

At three in the afternoon on Friday December 13th, 2019, I received a telephone call at work that Marie was found non-responsive and it appeared she may have had a seizure.

I raced out of work, and from my car spoke to the emergency room doctor, I assured her that Marie did not use drugs, but that she had been struggling for several months with depression. While driving and speaking to the nurse on the phone, I could hear the hospital team call a code as Marie went into another seizure.

When I reached the emergency room, I was told that Marie had overdosed on Benadryl. I alerted her father who found an empty container in his garbage: she had swallowed 98 pills, a total of 2,450 mg. of Benadryl. The lethal dose for a girl of her size is 500 mg. The time it would take to die from a lethal dose is two hours; Marie was already seizing with a heart rate of 179/160 (with a normal heart rate being on average 123/65) in the ER.

When I finally got to see her, Marie was hallucinating, moving her arms and legs involuntarily, unable to speak, and instead making gurgling sounds in her throat and struggling to swallow. I stood to her side and held her arms down, using my forearm to push her head flat on the pillow as she would strain to sit up, eyes glassy and unfocused. She was unresponsive, and I was informed that there were no interventions aside from giving her an anti seizure medication and something to lower her blood pressure; I was told she may not make it, that she was critical.

An ICU ambulance was sent for from 80 miles away, and it arrived within an hour, after Marie was intubated and provided a breathing tube; she was on life support and unconscious when they placed her on a Stryker stretcher and loaded her in the ambulance.

As I drove away from the emergency room, I could hear a woman with my voice screaming, and speaking unintelligibly to God in what sounded like a chant, over and over again, “please don’t let my baby die.”

Marie was in the pediatric intensive care unit on life support for the next four days. On day five, they removed the breathing tube, lifted the sedation, but she remained very ill. She spiked a fever almost immediately, could not speak, continued to hallucinate. I would bend down next to her lips to hear her barely whisper, and at first it was nonsensical, still in that world where she had been held hostage. When she finally became lucid, she had aspiration pneumonia, short term memory damage, and was weighing in with a BMI of 16.6.

When Marie was able to speak again, she recounted her suicide attempt, stating she was “never afraid,” and that she had told us she wanted to see a therapist or take medication to feel better, “and you didn’t do anything.” Oh, darling, I wanted to tell her, “I tried.” She had moments when she would say, “I still want to die,” and others in which she would stare into space, weightless and untethered, one foot in each world, it would seem.

Marie discharged home from the hospital after six days, with an offer for her to stay at the children’s hospital while waiting for an inpatient bed, where she would remain and be assessed over ten days.

As a psychiatric social worker with five years of working on an inpatient unit, I felt I could provide the safety and supervision at home that she would find there, without the additional trauma of potential seclusions and involuntary medication administration.

I blame myself, as if I should have held it off, should have known in advance, that she wanted to die. The biggest wager was thinking that she could wait for help, that a waitlist would open, and if I just looked at the locks on the box like Houdini, I’d find a way out. Instead, she found her own.