(1-13-20) The death of a 56 year-old homeless man, who was crushed to death, has outraged Brandan Thomas, director of a rescue mission in Winchester, Virginia. I recently posted a blog about a 12 day motorcycle ride that Thomas made to call attention to the plight of homeless Americans. Thomas is director of The Winchester Rescue Mission, which has beds for 32 men and recently opened a second location with beds for 15 women. Some 300 individuals in the Winchester are homeless. Thomas recently said it can take six months for someone who walks into his shelter with a mental health issue to get an appointment with a doctor.

The death of Michael Kenneth Martin was especially troubling to Thomas because he had arranged for Martin to receive Rescue Mission services once he was released from jail, but Martin was freed without the Mission being notified. The rescue mission is an outgrowth of Canvas Church, which Thomas started in 2013 in a Winchester garage. It has since grown to 200-plus in attendance. He is an example of the power of single individual to foster change in a community.

Homeless man’s death prompts call for change

Reprinted from The Winchester Star newspaper.

“This man is dead because he was mentally ill and was seeking out the best form of housing he could because we did not help him,” an emotional Thomas said at the end of the three-and-a-half-minute video.

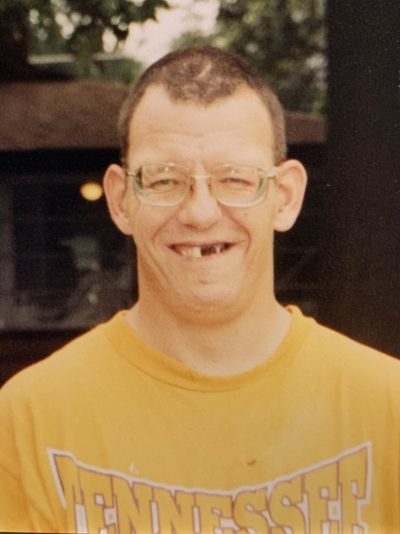

Michael Kenneth Martin

Photo provided by family

Michael Kenneth Martin, 56, was crushed to death on Jan. 1 while sleeping underneath a tractor-trailer in a Berryville Avenue parking lot. According to the Winchester Police Department, the driver, whose name was not released, got in the vehicle and pulled forward, not knowing that Martin was lying in front of the trailer’s rear tires.

Police reported that Martin smelled of alcohol and may have been intoxicated at the time of his death. Court records revealed that Martin had several previous convictions in Frederick County and Winchester general district courts for public swearing/intoxication and trespassing.

But the incident report and arrest logs only tell a small portion of Martin’s story.

Older brother Chris Martin, 57, of Brunswick, Md., said on Tuesday that Michael Martin, who was developmentally disabled and had the intellect of a 13-year-old, grew up in Bethesda, Md. He was kind and generous and supported himself as a landscaper before becoming homeless.

“Mike was a good person,” his brother said.

Chris Martin said his family enrolled his brother in at least 10 alcohol or mental health treatment programs, but Michael Martin’s desire to drink always compelled him to quit before substantial progress could be made.

Around 1995, Chris Martin obtained legal custody of his brother in hopes of getting him into a program he couldn’t voluntarily leave, but discovered that private programs were either unavailable or too expensive.

Michael Martin’s alcoholism and mental health had worsened by the time he moved to Winchester in 2017. From that point on, the only time Chris Martin heard about his brother was when police called to say he’d been arrested for public intoxication.

“It just progressed to a point where he didn’t want the help that was offered from us,” Chris Martin said.

Thomas said Michael Martin’s story exemplifies a situation that has become common in the United States.

“We have a mental illness crisis,” Thomas said on Tuesday during an interview in his office at the Winchester Rescue Mission on North Cameron Street, which provides shelter and services to homeless individuals in the Northern Shenandoah Valley. “We don’t have a place for [economically disadvantaged] people with mental illness to go; we don’t have a system set up for [homeless] people with mental illness to get help.”

According to the national nonprofit Mental Illness Policy Org., 4% of all Americans over the age of 18 suffer from a debilitating mental illness like schizophrenia, depression or bipolar disorder. If these people don’t receive ongoing treatment, their conditions can cause mania, hallucinations, paranoia, an inability to control their own thought processes, and more.

Sometimes, a severe mental illness can cause a condition known as anosognosia, which convinces a person that they’re perfectly fine and don’t need help. Mental Illness Policy Org. reports that consequences for seriously ill individuals who do not receive treatment can include homelessness, incarceration, homicide and suicide.

“There are 140,000 mentally ill people that are homeless right now in our country,” Thomas said. “Another 392,000 mentally ill individuals are in jail. We’re relying on the jail system to be the mental health institution, and they’re not trained to do that.”

The current methods for treating severe mental illnesses among the nation’s homeless and disadvantaged populations are underfunded and overwhelmed, Thomas said. As a result, people with untreated conditions often go unnoticed by communities until they break a law or suffer a traumatic event.

Michael Martin was an inmate at Northwestern Regional Adult Detention Center in November when Thomas first met him, and the Winchester Rescue Mission was in the process of devising a treatment plan for him once he was released from custody.

“I was excited about the opportunity to get him help,” Thomas said.

Michael Martin was expected to be held on a public swearing/intoxication charge until a trial could be held in February, but the court date was moved to mid-December without anyone from the Rescue Mission knowing about it. He was fined and set free.

“Next thing you know, I find out from the paper that he’s been run over,” Thomas said.

While Michael Martin apparently fell through the cracks, there is a system in place to help mentally ill homeless people. Police can use an eight-hour emergency custody order to temporarily detain homeless people that may pose a danger to themselves or others, or display an inability to care for themselves. Following a psychiatric examination, those who are deemed to be mentally ill can be held for up to 72 hours before a judge decides if they’re healthy enough to be released.

In Winchester and Clarke and Frederick counties, those people are taken to the Crisis Intervention Team Assessment Center at Winchester Medical Center. Since its opening in July, 92 people with emergency custody orders have been evaluated at the facility, according to supervisor Donna Trillio.

A psychiatric intervention would have benefited Michael Martin, Thomas said. Instead, he was left to make his way through life on his own, dealing with a severe mental condition by self-medicating with alcohol.

“It’s like watching somebody bleed to death,” Thomas said.

The end result was that he died on New Year’s Day while sleeping in the best place he could find on a cold winter night.

“My goal,” Thomas said, “is that maybe his death is the thing that will cause people to pause for a moment to think and even advocate by going to their elected officials and saying, ‘Something’s got to change.’”

— Contact Brian Brehm at bbrehm@winchesterstar.com and Evan Goodenow at egoodenow@winchesterstar.com