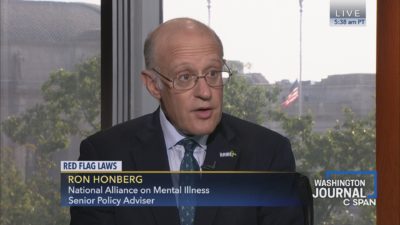

(4-2-20) With all of our attention on the pandemic, a U.S. Supreme Court decision about the insanity defense last week didn’t attract much attention. As long-time mental health advocate and attorney Ron Honberg reports it should have!

Kahler V. Kansas Ruling Says States Can Separately Define Insanity In Criminal Cases.

By Ron Honberg, J.D.

A divided U.S. Supreme Court issued a ruling last week that essentially said states can eliminate the option of insanity as a defense regardless of how sick someone might be.

There is an old adage that “hard cases make bad laws.” What this essentially means is that cases with unusual facts sometimes lead to decisions that create bad legal precedents for a large number of people.

Kahler v. Kansas may prove that point.

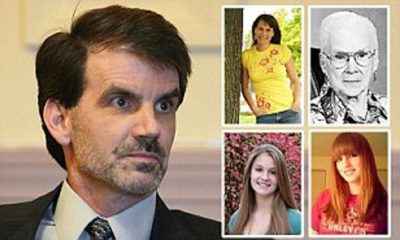

No one disputes that James Kraig Kahler committed a horrific crime. He shot to death his estranged wife, their two daughters, and his wife’s mother, sparing only their nine-year-old son who witnessed the shootings .

Kahler did not have a previously documented history of mental illness.

An engineer by training, he was the Director of a public utility in Columbia, Missouri. But, after his marriage began deteriorating, Kahler showed signs of unraveling. He lost his job and he began behaving in an increasingly angry and erratic manner, especially towards his family.

After the murders, Kahler was evaluated by two forensic psychiatrists, one for the defense, the other for the prosecution. Although the two psychiatrists disagreed on the severity and impact of his conditions, both concluded that he “exhibited major depressive disorder, as well as obsessive-compulsive, borderline, paranoid and narcissistic personality tendencies.”

The defense psychiatrist concluded that Kahler did not seem to understand what he had done and “could not let himself feel any emotions about (their) deaths” because of that. Of course, the prosecutor’s psychiatrist disagreed.

Kahler’s attorney said his client should be found not guilty by reason of insanity because, due to his mental illness, he was not able to think or act rationally at the time he committed the crime – a standard argument in insanity cases.

Kansas, however, had amended its insanity defense statute in 1995, stating that a jury didn’t need to consider whether a person was rational when they committed a crime.

Because of that change, the trial judge ruled that Kahler couldn’t use the insanity defense and jurors convicted him of first-degree murder and sentenced him to death.

Kansas is not the only state that has limited the use of the insanity defense in this way. Alaska, Idaho, Montana and Utah, also have changed their statutes. But this case is the first time the Supreme Court was asked whether these limitations that changed legal precedent are constitutional.

On March 23, 2020, the Supreme Court upheld, by a vote of 6-3, the constitutionality of Kansas’ law.

Writing for the majority, Justice Elena Kagan (joined by Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh and Thomas) declared that determining standards for insanity in criminal cases is best left up to each state’s legislature. In their majority brief, they referred to the difficulties involved when a defendant’s mental health is questioned – uncertainties about the human mind, disagreements among psychiatrists in diagnosing and determining best treatments for specific mental health conditions, and other factors in concluding that it would not be appropriate to reduce insanity to a “rigid constitutional mold.”

By upholding Kansas’ statute and by implication the similar standards contained in the laws of the other four states, the Supreme Court held that it is constitutionally permissible for states to so narrowly define insanity in their statutes as to make it virtually unavailable as an option for criminal defendants.

Andrea Yates Case Example

To understand the implications of this decision, consider the example of Andrea Yates. Ms. Yates intellectually understood that she had drowned her children. She even called the police to tell them that she had done so. But, she believed her act was necessary because of her delusions that killing them was the only way to save them from being possessed by the devil. She was found not guilty by reason of insanity under the law of Texas.

Now, this defense may no longer be available in states such as Kansas.

The majority did write that a defense can introduce testimony and evidence about the effects of mental illness on a defendant’s rationality and question the criminal culpability of their client at sentencing after a guilty verdict is rendered. For instance, a defense attorney could argue that his client should be sent to a forensic hospital, rather than prison. While that sounds fair, in my experience after decades of watching such cases, defendants are rarely sent to hospitals after being convicted of serious crimes such as first-degree murder. And, even when individuals are sent to hospitals, they can be returned to prison after their symptoms stabilize. They can even be sentenced to death.

The dissenting opinion in this case was authored by Justice Stephen Breyer, joined by Justices Ginsberg and Sotomayor.

Justice Breyer understands mental illnesses. He is married to a psychologist and in 2009, he joined other distinguished panelists including Nobel Laureate Eric Kandel, the late Fred Frese, Pete Earley and Professor Elyn Saks on the Minds on the Edge telecast on PBS, which explored in detail the effects of the active symptoms of severe mental illness on an individual’s state of mind and perceptions of reality, http://www.mindsontheedge.org/about/program/

In his dissent, Justice Breyer decries the majority’s disregard of 700 years of Anglo-American legal tradition, which acknowledged the accused’s mental state at the time of a crime needed to be considered. Justice Breyer warned that the majority “has eliminated the core of a defense that has existed for centuries, that the defendant, due to mental illness, lacked the mental capacity necessary for his conduct to be considered morally blameworthy.”

Defendants who raise insanity as a defense already had a difficult burden to meet in proving their cases before this ruling, which is why many defense attorneys chose not to raise insanity at trials. Oftentimes, jurors struggled when the evidence showed that a person had committed a crime yet shouldn’t be found guilty. They often didn’t understand how mental illnesses can distort thinking and mistakenly believed defendants would go free if they are found “not guilty by reason of insanity.”

Kahler Case Not Representative

Sadly, I do not believe this case was representative. While I do not question the severity of Mr. Kahler’s condition or his impaired state of mind at the time of his crimes, the facts of his case were particularly unsympathetic. He did not have a longstanding mental illness, nor a long history of erratic or irrational behavior. Indeed, he had been successful in his education and career and there was no apparent evidence in the record of previous hospitalizations or other evidence of severe mental illness in the years prior to this tragic case. His case also proved to be tabloid fodder.

I can’t help but wonder if Kahler’s insanity defense would have succeeded even in a state with a broad, expansive legal criteria for insanity. At the risk of Monday morning quarterbacking, this in my mind was not an ideal case to bring to the Supreme Court to resolve the critically important question of whether it is constitutional for a state to effectively eliminate its insanity defense. I don’t fault Kahler’s lawyer in any way for having tried on behalf of his client, but I wish that the facts would have been more sympathetic.

Hard cases make bad laws indeed.

The Supreme Court’s decision and the various briefs written in this case can be found at https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/19pdf/18-6135_j4ek.pdf

About the Author: Ron Honberg recently retired as the National Alliance on Mental Illness’s Senior Advisor on Policy and Legal Affairs. While at NAMI, he filed numerous briefs about mental health law. He remains active as a volunteer at NAMI – answering its’ HelpLine, and as a mental health consultant.

The NAMI HelpLine can be reached Monday through Friday, 10 am–6 pm, ET.

1-800-950-NAMI (6264) or info@nami.org