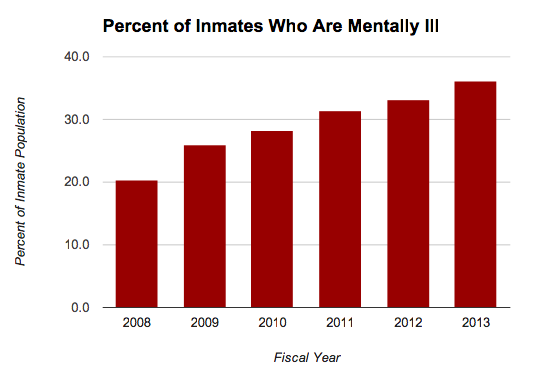

Chart courtesy of Oklahoma Watch

(Editor’s note: this is the first in a series about restructuring mental health services.)

(6-29-20) The idea that our jails and prisons are filling up with the seriously mentally ill at alarming rates because we have closed state hospitals is simplistic, according to a paper first published by Psychiatric Services and is part of the Think Bigger Do Good policy paper series which funds behavioral health research by Peg’s Foundation, the Thomas Scattergood Foundation, the Peter & Elizabeth Tower Foundation and the Patrick P. Lee Foundation.

Dr. Mark R. Munetz, the co-creator of the Sequential Intercept Model, and two of his colleagues, Natalie Bonfine and Amy Blank Wilson, write that we must consider other factors in addition to serious mental illnesses if we want to address the fact that 2.2 million Americans with mental illness are booked into jail each year and 365,000 currently are incarcerated.

Natalie Bonfine, an assistant professor in psychiatry at Northeast Ohio Medical University, is the primary author of “Meeting the Needs of Justice-Involved People With Serious Mental Illness Within Community Behavioral Health Systems.” For those unfamiliar, the Sequential Intercept Model is recognized nationally as the leading tool in identifying people with serious mental illnesses in the criminal justice system and finding appropriate places to intervene and get them into treatment.

The three researchers state that closing of public mental hospitals lead to “first-generation interventions” to reduce criminalization, such as pre-and post-booking diversion programs, mental health courts, specialized probation, forensic assertive community treatment teams and re-entry programs. But while these programs have shown promise, the authors write that “none has been able to achieve a sustained impact on criminal recidivism.”

Why? Because treating an individual’s mental illness is not enough.

At the top of the list of other contributing factors to incarceration and recidivism of persons with serious mental illnesses is substance use. Those with both mental illnesses and substance abuse return to jail more often and more quickly than those only with a diagnosed mental illness.

Other factors that are keeping Americans with serious mental illnesses revolving in and out of jail include:

“A history of antisocial behavior, antisocial personality pattern, antisocial cognition, and antisocial associates – called the ‘Big 4’ because they have the strongest association with continue justice involvement…”

The authors note that “poverty, homelessness, unemployment and low educational attainment” also make it difficult for those with serious mental illnesses to stay out of jail.

“Many people with serious mental illness live in environments and communities where crime, violence ambient substance use, and social disorganization are endemic, which can increate justice involvement.”

Research shows that an individual’s race and tough on crime policies such as three strike rules also contribute.

What is the solution?

The authors conclude that the reducing incarceration and recidivism rates of Americans with serious mental illnesses will only happen when we recognize that more than traditional mental health care is required. Services must be offered BEFORE police involvement (Intercept Zero) to meet ALL of the factors that lead to incarceration.

“For the integrated community behavioral health system to operate as an effective intercept zero, the system must both widen and deepen its array of services. To do so, it will need to master integration at multiple levels. Mental health, substance use, primary medical, criminogenic, and social needs all must be addressed in a coordinated and timely manner to achieve the desired goals or improved health, prevention of institutionalization (hospitalization and incarceration) and overall recovery. Incorporating multiple layers of integration into the operation of any one system is challenging, but this type of integration is an essential effort…and we believe it can be done.

The authors acknowledge that their call for integrated care before police involvement is “aspirational.”

…Although mental and substance use disorders and criminogenic needs all need to be addressed, efforts to make the behavioral health system the focal point for the provision of this care will likely encounter resistance. The community behavioral health system may not want to take on this challenge, the criminal justice system may not want to give up control, and social service agencies may not be prepared for the degree of collaboration needed…”

But they insist:

“If adequately supported, this system could provide accessible, effective, and criminologically informed services to address the clinical, criminogenic, and social support services needs of people with serious mental illness who are involved in the justice system. The goal is to identify people who would be best served in community settings and expand the continuum of services available within the behavioral health system to meet people where they live, work, and receive services. The role of the justice system will move toward collaboration and away from the need to build a parallel treatment system to address the treatment needs of justice-involved people with serious mental mental illness. We believe that this approach can improve individual and systems outcomes by preventing justice involvement, reducing service redundancy, and improving health and quality of life of people who are living in the community. All of society needs to take on the larger social issues that disproportionately affect people with serious mental illness.”

Their report can be summarized by one sentence midway in it: “People with serious mental illness have complex lives that are not defined by their mental illness alone.”