(7-6-22) After five years, I’ve resigned from the federal panel that advises the U.S. Congress about serious mental illnesses.

I was appointed to be the parent designee on the Interdepartmental Serious Mental Illness Coordinating Committee (ISMICC) when it was formed and held its first meeting on August 31, 2017.

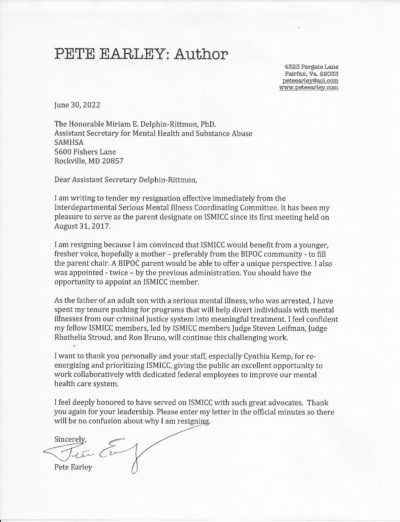

I am resigning because I believe ISMICC could benefit from a younger, fresh voice. In my letter, I urge Assistant Secretary for Mental Health and Substance Abuse Miriam E. Delphin-Rittmon, PhD., to appoint a mother, preferably from the BIPOC community, as my replacement, although I have no say in her decision.

Because of the structure of ISMICC, I was appointed to two terms by the previous head of SAMHSA. I want Dr. Delphin-Rittmon to be able to appoint an ISMICC board member of her choosing, especially since she has revitalized ISMICC after it was pushed to a back burner during the final years of the Trump Administration.

Being on ISMICC enabled me to push for reforms. But I also leave with disappointments.

ISMICC was created through the Helping Families In Mental Health Crisis Act. It is composed of federal officials representing the major federal agencies that deal with mental illness and substance abuse programs along with 14 non-federal members who hold specific seats on ISMICC – two seats for persons with lived experience with the rest divided among representatives from law enforcement, mental health providers, and mental health organizations. ISMICC’s mission is to offer advice and guidance to Congress about how to support recovery by coordinating federal services.

My Focus Was On Criminal Justice

As the parent member, I focused on the intersection of serious mental illnesses and the criminal justice system. ISMICC has issued two reports to Congress and, in both, I pushed for ZERO intercept (offering alternatives to calling the police when someone is in crisis), greater access to drop off centers (rather than jail and emergency rooms), more jail diversion programs, more use of speciality courts, more peers, and more programs to help those who become entangled in our system re-enter society and get community support for their mental illnesses, including jobs and especially housing.

I am proud that I was able to persuade the federal Bureau of Prisons to began participating in ISMICC (Congress failed to include it.) A recent report estimated 45 percent of federal prisons have mental health problems. The bureau is responsible for 226,000 prisoners.

Meanwhile, there are disappointments.

I pushed for an end of solitary confinement for individuals with serious mental illnesses and limiting restraints, but was unable to achieve either.

I am sad that ISMICC has failed to push for changes in federal HIPAA regulations that much too-often are used to block families from partnering with mental health professionals in providing care for someone with serious mental illnesses. Parents should be part of the healing process and that requires communication with mental health providers.

Nor has ISMICC addressed the need to revisit IMD Exclusion restrictions that continue to thwart efforts to build more, much needed emergency crisis beds. We simply do not have enough crisis beds because of this antiquated exception.

I also wish ISMICC would have focused more on the struggles that parents face trying to get meaningful care for their children and adolescents. As demonstrated most recently in the Ken Burn’s PBS documentary, Hiding in Plain Sight: Youth Mental Illness, young people are not receiving the care that they need in our nation. It is shameful.

I leave ISMICC thankful for being able to work with so many wonderful colleagues – both present and past – who are committed to helping those with serious mental health and serious emotional issues. They are a smart group.

While I am resigning, I will continue to advocate in other ways for individuals with mental illnesses who deserve much better than what we are currently offering them.

The struggle continues.