Sales video promoting BOLA Wrap by Wrap Technologies

(8-3-20) Three comments about law enforcement and state prisons.

What do you do when Crisis Intervention Team Trained Officers are criticized for violence?

Last Thursday’s blog post about four Springfield, Oregon police officers who fatally shot an unarmed young man with schizophrenia outraged many readers. What made the officers’ actions even more appalling was that all had undergone Crisis Intervention Team training and one of them was the department’s CIT trainer. None of the officers made an attempt to use his CIT training to de-escalate the situation, according to a detailed account written by Kimberly Kenny, whose brother, Patrick, was killed. Nor were any of the officers disciplined – one was given a medal by the police union. The police department and city settled a wrongful death lawsuit out of court for $4.5 million.

Based on Kimberly’s report, I would not want these officers responding if I called the police and requested a CIT trained officer to help me during a mental health crisis. There should be some way for officers and departments to loose the right to identify themselves as CIT trained when none of what CIT teaches apparently is practiced.

Lassoing individuals in a mental health crisis with bolas – humane or dehumanizing?

BolaWrap is a new device being pitched to police departments by Wrap Technologies as a humane tool to detain suspects who aren’t obeying orders. It is especially being marketed as a way to subdue those with mental illnesses who are in crisis.

I’m suspect. At first glance, this device strikes me as being dehumanizing and dangerous.

The Washington Post reports that the BolaWrap was created in 2016 and is modeled after the bolas used by gauchos to wrangle animals. A police officer can use the device to fire two Kevlar wires with fish hook – like fasteners at a suspect. The wires wrap around the suspect limiting use of arms or legs. In the company produced videos, the BolaWrap seems relatively safe. But Reporter Katie Mettler reported that when she watched a local demonstration, the BolaWrap impaled the hand of a volunteer who’d agreed to be shot. It drew blood. The demonstration videos that I watched showed the hooks being shot at volunteers wearing wearing long pants and long sleeved shirts. Where would those hooks go if you are shirtless or wearing short pants? Nor did I see any videos of individuals fleeing, which would impair shot accuracy.

Hooks at end of Kevlar lines hook onto suspect

BolaWrap is being touted as a non-lethal device safer than officers using a Taser and it clearly is better than having an officer shoot a suspect. According to the Post, BolaWrap went to market in 2018 but didn’t take off until Taser founder Thomas Smith signed on in 2019 as president of Wrap Technologies. “The company has been selling the device to law enforcement agencies for about a year, but over the past two months, Smith said, interest has increased … The Los Angeles Police Department’s BolaWrap pilot program began in February. Cmdr. Ruby Flores, who works in the training division, said the department has been working with BolaWraps since 2018 to help develop the product..Other departments in California, Florida and Texas have reported detainments or arrests made with a BolaWrap, Smith said, including the first documented successful deployment, by the Fort Worth Police Department during a SWAT call for a hostage situation.”

If you visit the Wrap Technologies you can read a list of police departments who are scheduled for a demonstration. Mental health advocates should insist that local police departments follow strict protocols if they intend to use the weapon on individuals with mental disorders. It is frustrating that new weapons to immobilize individuals in crisis are being marketed when less than 20 percent of police departments offer their officers Crisis Intervention Team training. Despite the failure of the Springfield Police Department, cited above, I have attending dozens of CIT award ceremonies and heard how officers have saved lives by convincing someone about to leap from a bridge to step back or calmly taking someone in crisis to a treatment center. While some question the effectiveness of CIT, I believe every law enforcement agencies should have its officers undergo it. The problem is weeding out those “warrior” officers itching for a fight who ignore what CIT teaches.

BolaWrap is not the first non-lethal device marketed as a way to safely subdue individuals with mental illnesses. In 2016, I wrote about how the New York Police Department had developed the EDP bag, short for Emotional Disturbed Person bag, or the “burrito.” It was a bag that those in crisis were sealed in – much like a duffel bag – under the pretense that it protected both the police and person entombed inside it.

The NYPD Burrito

How many of these devices would be marketed if the CEOs and sales force had to test them at least a dozen times on their own children, spouse/partner, or parents?

COVID-19 Spreading In State Prisons

A study by the Council on State Government shows that COVID-19 infections in state prisons is the highest it has been since the pandemic began. Texas, Florida, California, and Ohio are reporting the biggest outbreaks.

Individuals with mental illnesses are the fastest growing subpopulation in our jails and prisons. The number ranges between 16 to 20 percent of all inmates. Prosecutors and judges need to consider if they are giving the individual standing before them for sentencing a death sentence by sending them to prison during the pandemic. More communities need jail diversion programs for minor crimes by those who are mentally ill. You can read about inmates dying in the federal Bureau of Prisons here.

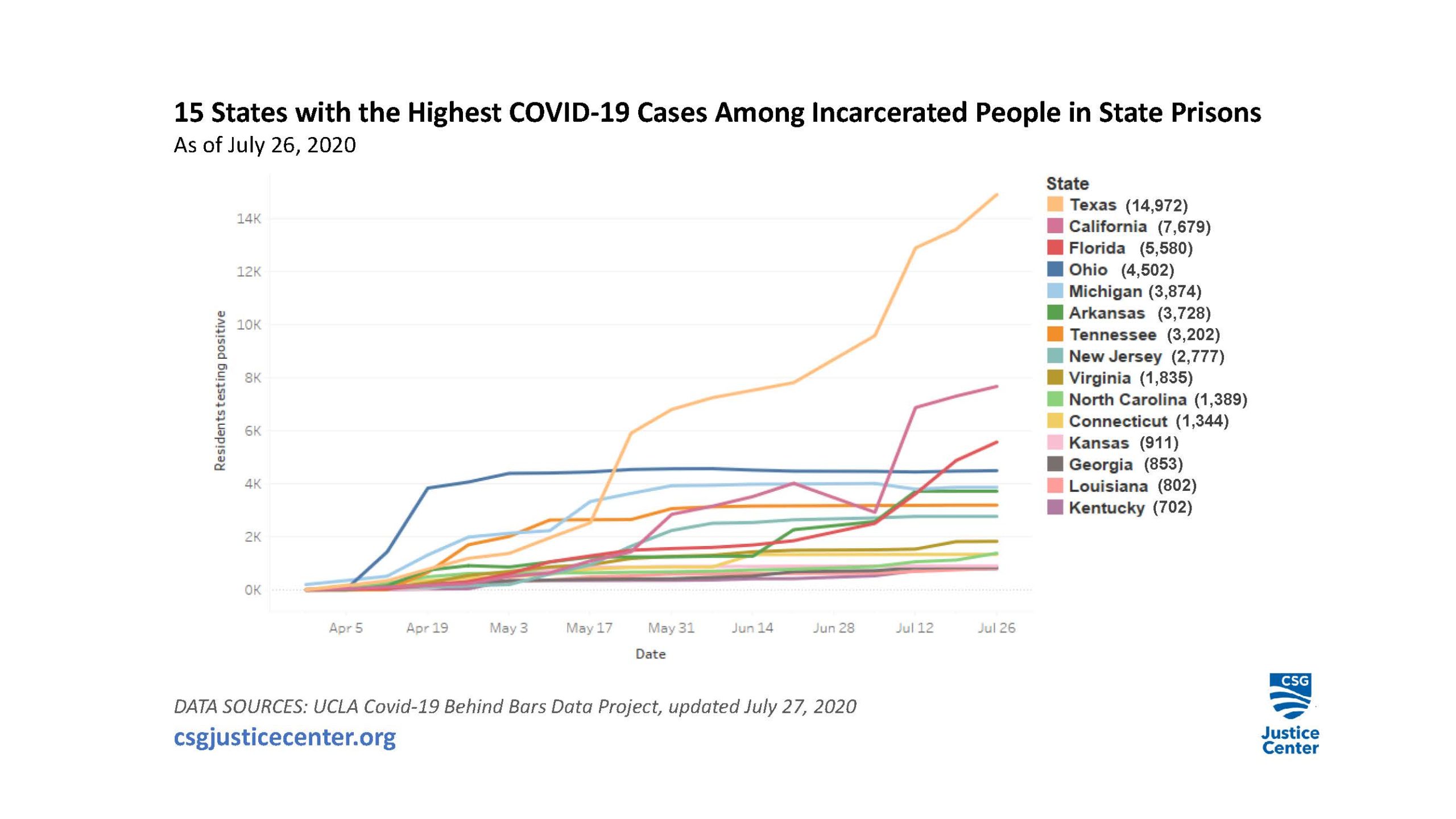

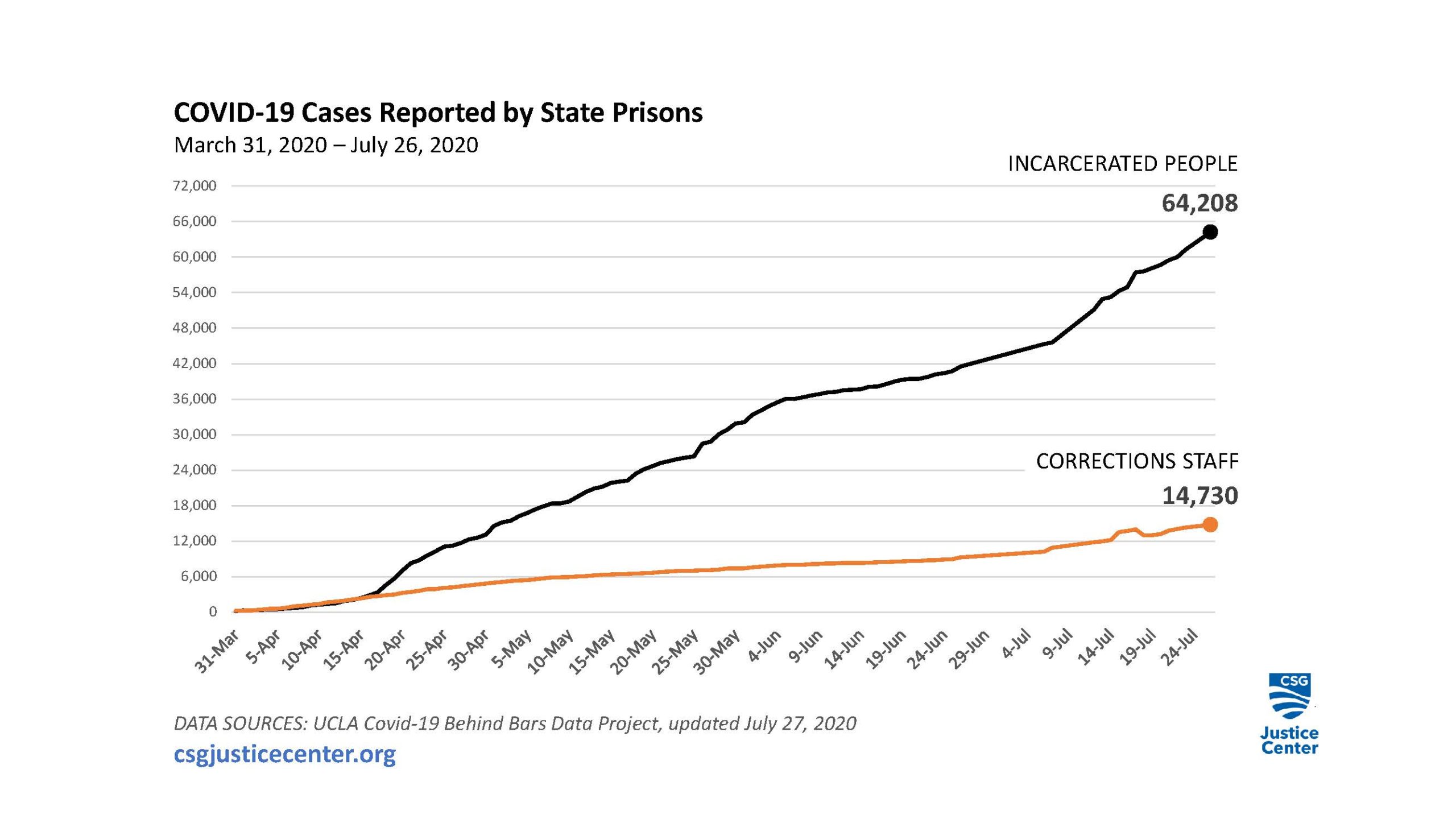

The following three graphs visualize the total number of reported cases in state prisons as of July 26; how infection rates differ among incarcerated people, corrections staff, and the general public; and data on 15 states with the highest cases in their prisons.

1. The number of COVID-19 cases in state prisons is at its highest point since the pandemic began, with more than 64,000 total cases.

In the past two weeks, between July 13 and July 26, cases grew by just over 11,300 in state prisons—from 52,901 to 64,208, a 21.4-percent increase.

2. The proportion of incarcerated people infected with COVID-19 in state prisons continues to grow, indicating that many states are struggling to contain the virus in their correctional facilities.

Early on, the outbreak was more pronounced among corrections staff, but it quickly began spreading to a broader population. On April 15, corrections staff were infected at more than double the rate of both incarcerated people and the general public. But as of July 26, incarcerated people were infected at more than four times the rate of the general public, and nearly two times the rate of corrections staff. Corrections staff are now infected at a rate of two and a half times that of the general public.

3. The top four states leading the country in COVID-19 infections among incarcerated people in state facilities—Texas, California, Florida, and Ohio—account for 50 percent of all state prison cases.

The total incarcerated population in these four states alone amounts to 34 percent of the total incarcerated population in state prisons nationwide. Caseloads in several states, including Minnesota, Ohio, and Tennessee, began to flatten in the late spring, which could reflect state testing practices or successful containment strategies.

For more information about COVID-19 in the criminal justice system, please visit our COVID-19 Assistance page.