Colorado Insane Asylum – State Hospital

(9-14-21) In 1957, a fourteen year old boy named Mike Trimble was committed to the Colorado State Hospital in Pueblo after sequential diagnoses of “retardation, schizophrenia and epilepsy.” Mike’s brother, Stephen, was only four years old. Ten years later, Mike was mainstreamed back to Denver but didn’t want anything to do with his family.

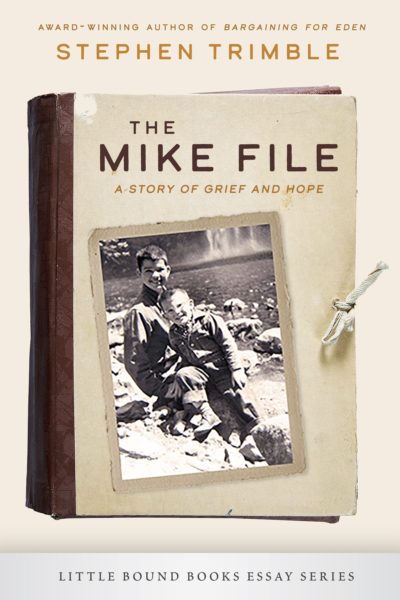

In a new nonfiction book, The Mike File: A Story of Grief and Hope, younger brother Stephen, searches for answers about what happened to his older brother.

My interest in Stephen Trimble’s book was piqued, in part, because as a teenager I spent a week at the Pueblo asylum. It was during the summer of 1969 and I was a volunteer there through my church. I mowed lawns and cut hedges in the morning and in the afternoon tagged along with a psychiatrist on his daily rounds. This was years before HIPAA and no one hesitated at having a naive teenager roaming the wards asking questions.

The hospital was in the midst of sending patients home as part of the coming national deinstitutionalization movement. In 1961, the hospital had hit a high of 6,100 patients. I spent my week observing two patients. The first was a woman who had been committed at her husband’s request. She had fought with him and seduced their teenage son to punish his father. The second patient was a young man – Chris – who’d been dropped off at the hospital as a toddler and grown up inside the asylum. By the time of my visit, doctors were convinced that the then forty-year old had never had a mental disorder. He’d been an unwanted child who was simply dumped at the doorstep. He had symptoms of Tardive dyskinesia even though records showed that he had not been heavily medicated and he acted as if he were sick because other patients had served as his role model. It was a horrific situation, which only became sadder when he was discharged to a nursing home. I heard later that Chris had died three years after I encountered him.

Although I was at the hospital only a week, my visit there left a lasting impression and vivid memories. I am glad that Stephen Trimble decided to investigate his brother’s life during this period in our history. And am grateful that he decided to share an excerpt.

The Mike File: A Story of Grief and Hope (an excerpt)

By Stephen Trimble

You step from your car, distracted, headed for an appointment. A homeless man approaches. Bearded, unkempt, wild-eyed. You know you should be empathetic, but he comes too close. No sense of boundaries, no filters, jumpy in his movements. You pull back, you stiffen, on alert, expecting a request for a handout or a disorganized rant about lurking CIA operatives.

You feel guilty, but you don’t want to get drawn into messiness. You nod, you smile tightly. You look away. You move on.

Mike may have had some of this look of The Other, even if I remember him cleaner, better dressed, and better groomed than most of the people we see walking on downtown sidewalks, conversing in erratic outbursts with unknown listeners. Most of us turn away from these people in need, no matter how forlorn they seem. We don’t want to get involved.

Mike never retreated from his painful decision to cut off contact with us. We honored his appeal to be left alone. And he wasn’t the only returning patient to lose connections with family. The vast majority of people released from the state hospital did not return home. They had no families to take them in.

In Mike’s day, nearly everyone leaving the hospital in Pueblo ended up in halfway houses, boarding houses, or, eventually, on the streets. In Colorado, the community-based services needed for effective housing and treatment couldn’t cope with the flood of patients migrating out of Pueblo. With time, resources grew ever more scarce.

Coming to Denver “paroled” as an ex-state hospital patient, Mike carried nearly the same stigma he would have endured if he’d been released from prison. The language we use to describe people like Mike matters. We react differently to “retarded and schizophrenic” than we do to “people with intellectual disabilities and psychiatric illness.”

When I was a kid, one way to cope with my brother’s banishment was to picture Mike living in the best possible situation for someone like him, a sort of boarding school, a place he accepted, adapted to, maybe even preferred. After he left the hospital and cut himself loose from us, I could imagine him as an independent actor, with a circle of similar folks to hang out with. But I never visualized details. I had no starting point.

Meanwhile, I took my peaceful and privileged life with our parents for granted. I acknowledged my brother just once a year. At least through high school, I sent Mike presents for Christmas and for his New Year’s Eve birthday. Aftershave. A carton of cigarettes. He sent a brief thank you. And then I returned to my classes, my friends, my enthusiasms, giving him no thought, sometimes for months.

The final diagnosis in Mike’s chronology at discharge in spring 1967 brands him with a lifetime label, “Schizophrenic reaction, residual type.”

The patchy record makes no mention of “retardation.” Psychiatric disorder evidently trumped intellectual disability. The very last line marks his official discharge from the hospital in October 1967, a year after his arrival in Denver: “Condition, Improved—Administrative Discharge.”

How “improved” was he? What happened to his “schizophrenia?” Controlled? No reports from Pueblo can tell me. And Denver General Hospital has no files from outpatients who used their services so long ago. The record lists two last Capitol Hill addresses with October dates. And that’s it. Mike disappears.

LET IT BE

On a cold winter-gray day in 1970, I drive through downtown Denver in our inelegant old pinkish-tan 1962 Dodge Dart, the family car now passed on to me. I’m home from college on winter break, running errands. Multi-lanes of traffic carry me down Broadway, through the heart of the city, the heart of the state. The Capitol rises to my left, its gold dome incandescent in low-angled light. Off to the right, khaki-colored grass leads past leafless black branching trees reaching skyward, the imposing Civic Center behind. Steam plumes from vents. The breath of the city.

A line of people stands on the curb, bundled up for winter, waiting, watching, or maybe just killing time. And there’s Mike, at the front of a cluster of folks at a bus stop. He wears that same scowl of unhappiness I remember. He’s a slouching column of dark tallness, a cigarette dangling from his fingers.

I slow down, I grip the wheel, hesitant, agitated, but can’t quite get myself over to the curb. I want to stop. I’m scared to stop. My AM radio blasts The Beatles—The Long and Winding Road that leads me to your door… and Let It Be. Conflicting advice. No help there.

I’m riveted to Mike as I roll by. He doesn’t make eye contact. Even if he saw me, he might not recognize me. Mike wanted nothing to do with us, right? What in the world would I say?

I don’t pull over, roll down the window, call to him.

Before I know it, I’m past, still clutching the wheel. I do not drive around the block to give myself a second chance to push through my uncertainty, stop, park, hop out of the car, and catch Mike before he moves on, boards his bus, disappears. I let the current of traffic carry me downstream, south along Broadway, away from my brother.

My recollection of this encounter moves, like a scene from a movie, a YouTube video clip. It’s one of those permanent memories generated when you lock onto a scene, staring so hard at someone or something that there’s a taut line carrying the image right into your brain where it remains forever vivid.

After so many years of Mike existing as an abstract fact in the nether reaches of reality, without detail or motion, this chance sighting of my brother takes on the full resonance of regret. I remember the moment with utter clarity because I’m so mortified by my failure to call out to him. I simply don’t have the confidence, the empathy, the kindness, the agency, to stop.

LOVE, WORK, PANCAKES

A widely-quoted aphorism from Freud tells us that “Love and work are the cornerstones of our humanness.” Mike, as far as I know, had few avenues for either.

As I try to conceive of Mike’s happiness, how he structured his life to meet his needs as best he could, I think of Rain Man. Mike wasn’t Raymond Babbitt, the Rain Man so memorably acted by Dustin Hoffman, and I’m not Charlie, the arrogant hotshot younger brother played by Tom Cruise. But Charlie spends a week with his savant brother on their memorable road trip and makes “a connection.” That experience transforms their relationship. Charlie, self-involved and selfish, for the first time can say of Raymond, the brother he had forgotten, “This is my family.”

At the end of the movie Charlie harangues Raymond’s doctor. “Did you spend 24 hours a day, seven days a week with him? Have you ever done that? When we started out together, he was only my brother in name. And this morning… we had pancakes. I made a connection.”

It never occurred to me to seek out Mike, for pancakes, for connection, for anything at all. His place in my life was defined by a rote explanation whenever I got around to mentioning him. The best I could muster was to add new phrases to my mantra as Mike added new chapters in his life.

“I have a retarded brother—a half-brother. He left home when I was six when he was swept away by schizophrenia. He spent years at the state hospital and now lives in a halfway house and wants nothing to do with our family.”

His existence barely mattered to me in these years. But his existence always mattered to our mother.

So did his death.

About the Author:

This excerpt comes from Stephen Trimble’s memoir about his brother, The Mike File: A Story of Grief and Hope, to be published by Homebound Publications on September 28th. Ron Powers, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of No One Cares About Crazy People, says of the book: “Trimble adds a new voice of eloquent witness to the growing literature of severe mental illness. With restrained grief and unrestrained remembrance, he reclaims in words his lost, loved and loving brother. He reminds us that the mad among us are human—and in many ways versions of ourselves.”

As writer, editor, and photographer, Stephen Trimble has published 25 award-winning books during 45 years of paying attention to the landscapes and peoples of the Desert West. Trimble grew up in Denver and makes his home in Salt Lake City and in the redrock country of Torrey, Utah. For more about his work, see www.stephentrimble.net.