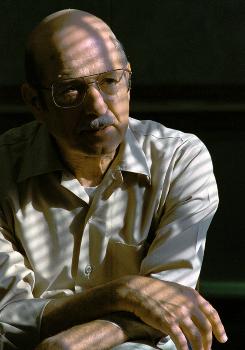

Arthur James Walker, one of the major characters in my first book, FAMILY OF SPIES: Inside the John Walker Spy Ring, is dead.

Arthur James Walker, one of the major characters in my first book, FAMILY OF SPIES: Inside the John Walker Spy Ring, is dead.

According to the federal Bureau of Prisons website, he died on July 7th, at a low level security prison in Butner, North Carolina. He was 79 years old and had served 29 years in prison after being convicted of committing espionage. He was one month away from a parole hearing. I’ve been told the cause of his death was acute kidney failure. I’ve also been told by a family friend that Art actually died on July 4th, Independence Day, and that the BOP simply did not get around to filing its paperwork until three days later.

Walker was the older brother of John Anthony Walker Jr., who remains in poor health, at the same Butner prison. John, who is 76, is scheduled for parole on May 20, 2015, but is in the later stages of throat cancer, according to a family friend.

John Walker Jr. was arrested by the FBI in May 1985 in a Maryland suburb where he had gone to deliver classified Navy documents to a Soviet Union contact. John had been spying for the KGB from late 1968 until 1985 and had recruited his own son, Michael Walker, brother Arthur Walker and Jerry Whitworth, a friend, to join him as spies. All were in the Navy. The arrest of the Walker Spy Ring sparked what is known as the Year of Spy. Up until that arrest, it was generally believed that Americans didn’t betray their country. Eight major traitors were arrested after the Walker Ring in a single year. The Walker Spy Ring was called the most damaging spy ring in American history.

I first met Arthur in the jail in Virginia Beach after his arrest when he agreed to grant me an exclusive jail house interview for The Washington Post Magazine in 1985. It was that interview that led to me getting into see John who was being held in a jail in Ekton, Maryland. John didn’t want to miss out on being interviewed. He was the star, not his brother.

From the moment I met Arthur, I felt that he was naive, a trait that became obvious when he was put on trial. Art wore a toupee and when prosecutors asked one of their witnesses if they could point out Art for the jury, the witness became confused. Because Art’s toupee had been taken from him and he was bald in the courtroom, the witness didn’t recognize him. At that point, Art raised his hand and waved at him, helping prosecutors.

He showed that same naivete in his dealings with the FBI. The agents who ultimately arrested him, told me that they didn’t have a case against him until he voluntarily began talking to them in a series of interviews that lasted more than thirty hours — without a lawyer being present. He admitted photographing two classified documents while he worked at defense contractor in return for John paying him $2,000. Even then, prosecutors weren’t certain they had enough to convict him so they called his wife, Rita, to appear before a federal grand jury in Baltimore. She broke down in tears at the federal courthouse and Arthur, who had driven her there, voluntarily agreed to take her place, further sealing his fate.

His court appointed attorney, Samuel H. Meekins, Jr., would later tell me that his client had literally talked his way into being arrested.

After he was, Arthur wanted to cut a plea deal to spare his family the embarrassment of going to trial, but prosecutors refused to sign off on any such arrangement.

“We were not going to give up the public’s right to see into an espionage case,” Stephen S. Trott, an assistant attorney general at the Justice Department, explained. “You don’t put a knife in your country’s back and come in and ask for some kind of deal.”

In truth, the Justice Department wanted Arthur to go on trial so it would reveal how good of a case it had against John. It wanted to crucify him, as one government official told me. At the time, John was refusing to cooperate and Trott was trying to get him to agree to a plea deal in return for his cooperation. The FBI wanted to know exactly what the spy ring had given to the Soviets and prosecutors also needed John’s help to arrest and convict Jerry Whitworth. Eventually, John agreed to a deal in return for the government going easier on his son Michael, who was paroled in Feburary 2000 after serving 15 years in prison. Jerry Whitworth got the longest sentence of the four spies. He is 74 and will not complete his sentence until October 2, 2048, unless the government paroles him, something that it has refused to do for everyone except Michael Walker.

John recruited his brother as a spy after Arthur started a business that failed and went into debt. John told him that stealing information from a Virginia Beach defense contractor would be an easy way for them to earn extra cash, but after deliverying two documents, Arthur got cold feet and John lost interest because the information that he could steal was largely useless.

Bob Hunter, the FBI agent who interrogated Art Walker always believed that he knew more than he was admitting. Hunter became convinced that Arthur was actually the first family member to spy while he was stationed at submarine base in New England during the early 1960s several years before John contacted the KGB at the Soviet Embassy in Washington D.C.. But Hunter was never able to prove those suspicions.

I remember clearly the night that Meekins took me into the jail to talk to Art after he had been found guilty and was waiting to be sentenced.

“What’s the worst I can expect, Sam, from the judge?” he asked. “What do you think, maybe a two year suspended sentence? I won’t have to go to prison, will I? I mean, come on, I didn’t pass anything that was really valuable to John. The judge has got to realize that.”

After Art was returned to his cell, Meekins and I both lingered in the jail’s parking lot, completely stunned at how naive Art was. I told Meekins, “He just doesn’t get it, does he? Art will never be paroled.”

Meekins, a Vietnam Veteran who had fought during the bloody Tet Offensive, replied, “If you define a spy as someone who intentionally set out to injure his country or to help a foreign power, then Arthur Walker isn’t a spy…. Arthur did it because he wanted to please his brother. He did it for John.”

Even after he was convicted, Art couldn’t shake his brother’s shadow. In September 2010, I wrote an Op Ed for USA TODAY in which I argued that Art should be paroled. He’d served enough time for the crime that he’d committed. I pointed out that the most the government could show was that he gave the KGB schematics of a 20-year-old Navy boat. The drawings were so routine, the Navy classified them at its lowest level, and the retired KGB general who had overseen the Walker ring dismissed them decades later as “worthless.” Yet, each time Art came up for parole, the government claimed in letters to the parole board that Art was just as damaging a traitor as his brother who later admitted giving more than a million classified documents to the KGB.

That claim was nonsense. Yet it stuck. I’m not dismissing what Art did but there was never any evidence that his spying harmed anyone except himself. It destroyed his reputation, his family which became alienated from him, and led to him spending the remainer of his life in prison.

I believe this blog will be the first to announce his death. I will read the news accounts that follow this blog with interest. My guess is that most stories about Arthur will say more about John than him.

Even in death, he will remain in John’s shadow.