(3-16-18) From My Files Friday: I posted this segment about the need for mental health reform by John Oliver three years ago and it remains one of the best.

Published by The New York Times, March 3rd, 2018

They met on a rainy morning several years ago, at the base of the Helmsley Building in Midtown Manhattan. As others hurried to work, Pamela J. Dearden, an executive with JPMorgan Chase, noticed a woman, unperturbed by the rain or her surroundings, standing on a 36-square-foot sidewalk grate she had chosen as her home.

Ms. Dearden, known to everyone as P.J., offered her umbrella to the woman, who took it and thanked her.

A friendship blossomed. P.J. would often stop to talk with the woman, who sat amid shopping bags, books, food containers and a metal utility cart. P.J. admired her hardiness, but also her smile, her soft features and her humor. If the woman was sleeping or talking loudly to herself, P.J. held back, but other times she engaged her in short conversations, which could go into unexpected places.

The woman’s name was Nakesha Williams. She said she loved novels, and they discussed the authors she was reading, from Jane Austen to Jodi Picoult. She and P.J. chatted as time allowed, or until Nakesha veered into topics that hinted at paranoia: plots and lies against her. Yet, P.J. realized she knew little about Nakesha, and she wondered about her past.

Nearly three decades earlier, another woman took notice of Nakesha, then an 18-year-old college freshman, and considered her seemingly boundless future.

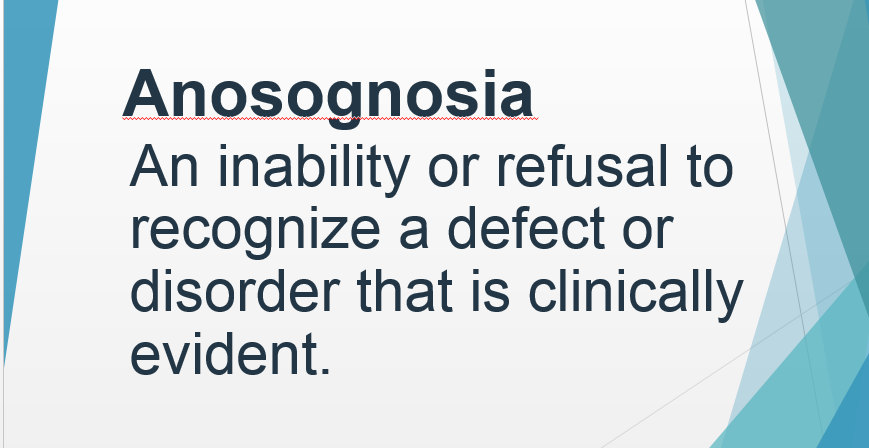

There’s no controversy here. People with psychotic disorders sometimes don’t know they are suffering from a mental illness, and there really is nothing to argue about. And yet, the word “anosognosia”—meaning the patient is unable to see that he is ill—is a charged word.

Why is that? Let me talk a little about the history of this word and the political meaning it has taken on.

Anosognosia is a term that was coined in 1914 by a Hungarian neurologist named Joseph Babinsky. Babinsky noticed that sometimes after a stroke, people are unaware of their deficits. This is presumed to be a result of pathophysiologic changes in the brain, and not the psychological defense mechanism of denial. There is not a precise anatomical finding that predicts anosognosia: you can’t look a patient with anosognosia and say, “ah, the MRI will show a lesion in X area of the brain.” Though certainly, some deficits are more likely to include anosognosia than others.