(6-30-17) I subscribe to The Atlantic and admire its often courageous and always thoughtful journalism. It recently published a profile of Tom Insel, former head of the National Institute of Mental Health, whom I first met in 2006 after my book was published when he asked me to speak at NIMH. A favorite at mental health conventions, Insel is one of the kindest and most thoughtful advocates whom I’ve had the pleasure of knowing. Here’s an excerpt.)

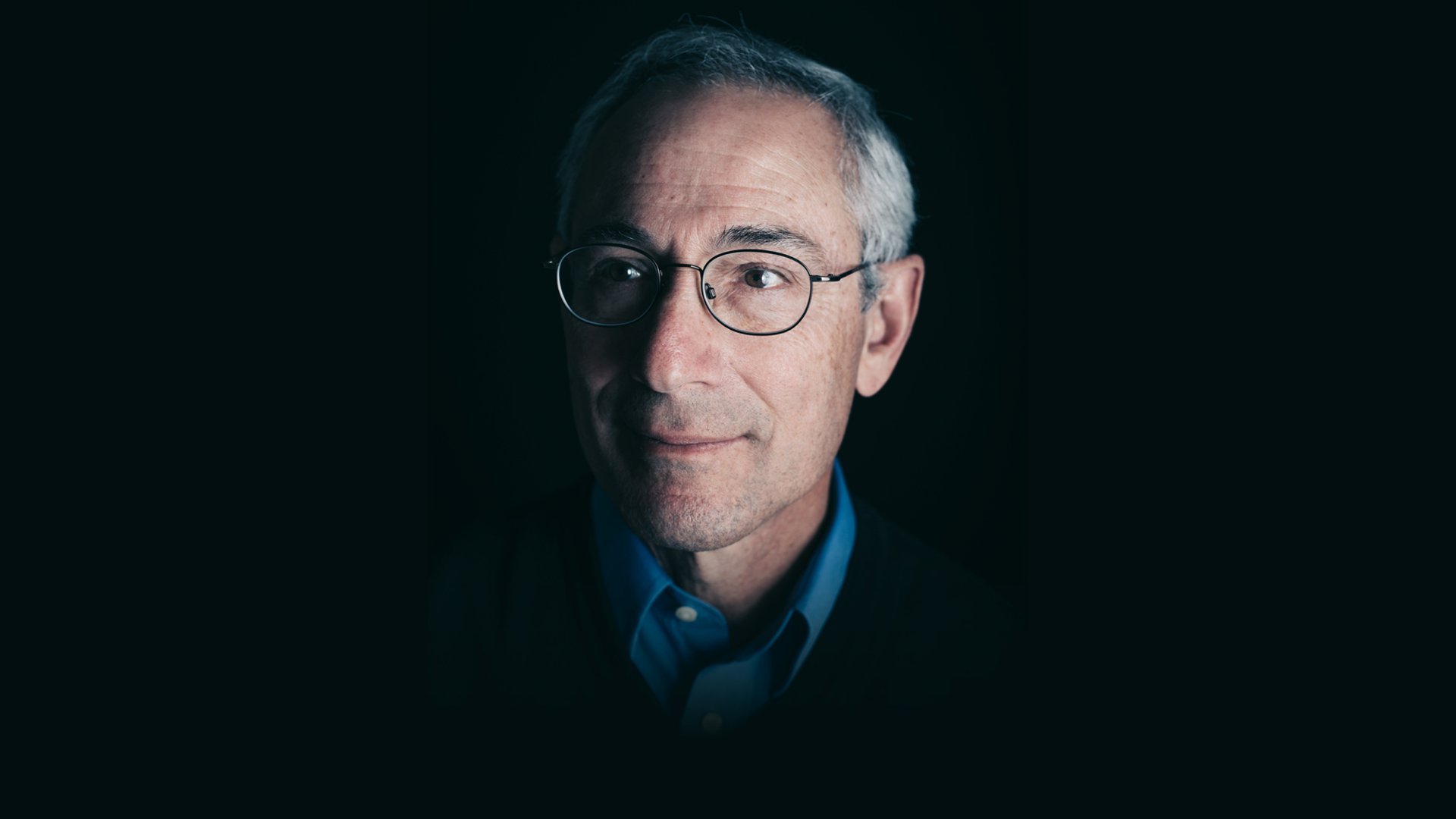

The Smartphone Psychiatrist

Frustrated by the failures in his field, Tom Insel, a former director of the National Institute of Mental Health, is now trying to reduce the world’s anguish through the devices in people’s pockets.

Published in the Atlantic. Written by:DAVID DOBBS

Sometime around 2010, about two-thirds of the way through his 13 years at the helm of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)—the world’s largest mental-health research institution—Tom Insel started speaking with unusual frankness about how both psychiatry and his own institute were failing to help the mentally ill. Insel, runner-trim, quietly alert, and constitutionally diplomatic, did not rant about this. It’s not in him. You won’t hear him trash-talk colleagues or critics.

Yet within the bounds of his unbroken civility, Insel began voicing something between a regret and an indictment. In writings and public talks, he lamented the pharmaceutical industry’s failure to develop effective new drugs for depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia; academic psychiatry’s overly cozy relationship with Big Pharma; and the paucity of treatments produced by the billions of dollars the NIMH had spent during his tenure. He blogged about the failure of psychiatry’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders to provide a productive theoretical basis for research, then had the NIMH ditch the DSM altogether—a decision that roiled the psychiatric establishment. Perhaps most startling, he began opening public talks by showing charts that revealed psychiatry as an underachieving laggard: While medical advances in the previous half century had reduced mortality rates from childhood leukemia, heart disease, and aids by 50 percent or more, they had failed to reduce suicide or disability from depression or schizophrenia.