(8-31-18) From My Files Friday. I receive emails each week from parents seeking advice. This blog that I first posed eight years ago still rings true.

Helping Someone Who Has A Mental Illness: Lessons I’ve Learned

It’s difficult helping someone with a mental illness.

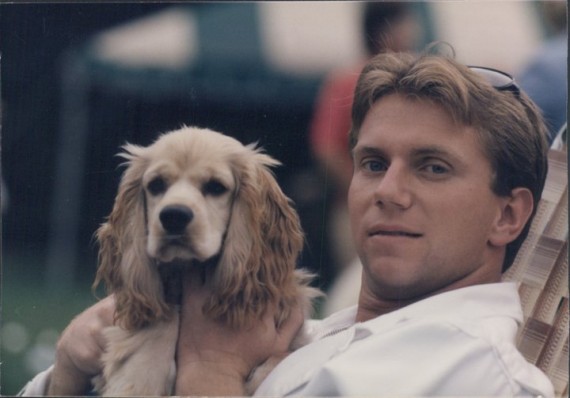

My relationship with my son, Kevin, has not always been easy. Those of you who have read my book know that I was forced to lie about him threatening me in order to get him taken into a hospital rather than put in jail. During a later break, I called the police and my son was shot twice with a Taser. These events hurt parent-son relationships.

So what have I learned?