everywhere he could. He was caught several times and when he refused to stop, he was beaten by a police officer before being booked into the Miami Dade County Jail. That’s where I met him.

everywhere he could. He was caught several times and when he refused to stop, he was beaten by a police officer before being booked into the Miami Dade County Jail. That’s where I met him.Mental Illness, Money, and Cheats

everywhere he could. He was caught several times and when he refused to stop, he was beaten by a police officer before being booked into the Miami Dade County Jail. That’s where I met him.

everywhere he could. He was caught several times and when he refused to stop, he was beaten by a police officer before being booked into the Miami Dade County Jail. That’s where I met him.Of Your Books, Which Is Your Favorite?

It’s a question I get asked a lot.

Answering it isn’t as easy as you might think. For an author, picking a favorite book is a little like asking a father if he loves one of his children more than the others. That’s an exaggeration, of course, but when you spend several years of your life consumed in writing a book, the finished manuscript becomes much more to its creator than ink, paper, or in today’s world, electronic text.

NAMI Changed My Life

When I was a Washington Post reporter, I did not believe in joining groups or organizations. I needed to be independent in order to be objective. Then my son, Mike, got sick and the first thing I did after I finished writing my book, CRAZY: A Father’s Search Through America’s Mental Health Madness, was join the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI.)

Why?

What I’d do differently!

Since the publication of my book, CRAZY: A Father’s Search Through America’s Mental Health Madness, I have been fortunate enough to speak in 45 states (Yes, I still am waiting for invitations from groups in Oklahoma, Nevada, Mississippi, Alaska and Hawaii, hint, hint) and I have toured dozens of successful treatment programs. Sometimes readers ask me what I would do differently if I were given a chance to rewrite my book. It is an interesting question because I have learned so much and met so many fascinating people during the past several years.

Since the publication of my book, CRAZY: A Father’s Search Through America’s Mental Health Madness, I have been fortunate enough to speak in 45 states (Yes, I still am waiting for invitations from groups in Oklahoma, Nevada, Mississippi, Alaska and Hawaii, hint, hint) and I have toured dozens of successful treatment programs. Sometimes readers ask me what I would do differently if I were given a chance to rewrite my book. It is an interesting question because I have learned so much and met so many fascinating people during the past several years.

The first thing I would do is change the title.

Pete Speaks in Brazil, Confronts Anti-Psychiatry Officials on Mental Illness

Brazil’s most prominent psychiatrist, Dr. Valentim Gentil, a professor at the Instituto de Psiquiatria, invited Pete to give several lectures to doctors, lawyers, students, and politicians in Sao Paulo and Brasilia after CRAZY: A Father’s Search Through America’s Mental Health Madness was published in Portuguese.

Brazil’s most prominent psychiatrist, Dr. Valentim Gentil, a professor at the Instituto de Psiquiatria, invited Pete to give several lectures to doctors, lawyers, students, and politicians in Sao Paulo and Brasilia after CRAZY: A Father’s Search Through America’s Mental Health Madness was published in Portuguese.

Brazilians are interested in the issues raised in Pete’s book, especially the closing of state hospitals without creating adequate mental health care services in communities. The Brazilian Ministry of Health has been under the leadership of anti-psychiatry officials for several years and has been closing mental hospitals.

During the 1960s, Thomas Szasz directed what became known as the anti-psychiatry movement in the US. He claimed mental illnesses were not biologically based brain disorders but myths created by psychiatrists. As explained in Pete’s book, Szasz described schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression as alternative ways of thinking. Overseas, Michel Foucault in France, R.D. Laing in Great Britain, and Franco Basaglia in Italy, championed many of the same anti-psychiatry rhetoric. About a decade ago, Brazil began applying Basaglia’s Italian doctrine. The head of its Ministry of Health has stated publicly that all hospitals should be closed because there is no mental illness in Brazil.

The translation of Pete’s book — Loucura: A Busca De Um Pai No Insano Sistema De Saude — sparked debate between anti-psychiatry leaders and Pete after Brazil’s Procuradoria Geral da Republica (the equivalent of the U.S. Attorney General of the United States) invited Pete to lecture in the nation’s capital to Brazil’s national legislature. Pete’s remarks were simultaneously translated and broadcast on national television. Afterwards, he answered questions from anti-psychiatry officials and explained that neuro-transmitter discoveries and schizophrenia twin registries have offered support that schizophrenia is biologically based. He added that the National Institutes of Mental Health classifies schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression as medical illnesses and diseases.

Veja, the largest magazine published in Latin America with 1.3 million readers, published an article about Pete‘s visit, book, and his calls for reform. Dr. Gentil appeared with Pete at several lectures and noted that in Sao Paulo City (population 12 million) there are more than 1,500 persons with chronic schizophrenia who are not being treated because of a lack of services and 15,000 homeless, most with untreated mental illness.

Here is an english translation of the article:

When the Love of a Father is Not Enough

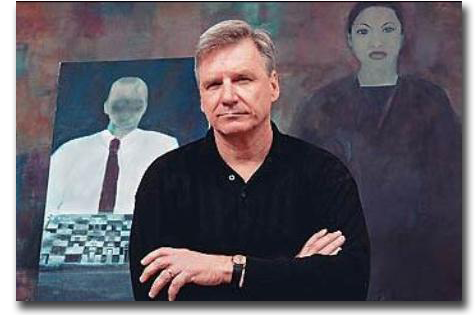

The American writer Pete Earley, of 57 years, specializes in the judiciary of his country. The most recent of his twelve books is based on personal experience. Just published in in Brazil, CRAZY: A Father’s Search Through America’s Mental Health Madness (Artmed, 375 pages) tells the story of his son Mike, who has bipolar disorder.

The American writer Pete Earley, of 57 years, specializes in the judiciary of his country. The most recent of his twelve books is based on personal experience. Just published in in Brazil, CRAZY: A Father’s Search Through America’s Mental Health Madness (Artmed, 375 pages) tells the story of his son Mike, who has bipolar disorder.

Besides telling the story of a sensitive father faced with the illness of a child, Earley writes critically about how U.S. laws deal with the mentally ill. Reforms during the 1960s, closed state hospitals, causing thousands of psychiatric beds to no longer exist and a majority of patients to be left untreated – a situation which Brazil now faces.

At the invitation of the Institute of Psychiatry, University of São Paulo, Earley spoke and engaged in a series of debates about this problem last week. Before embarking for Brazil, he was interviewed by VEJA reporter Adriana Dias Lopes, from his home in Fairfax, in the state of Virginia.

The Diagnosis

The first symptoms appeared in 2000, when Mike was 22 years old and studying in the school of arts at the Pratt Institute in New York. One weekend he called his father and said that he had taken five homeless men to breakfast at McDonald’s because he wanted to talk to them. Soon after that, Mike said he was not sure whether he had actually taken the men to breakfast or dreamed it.

His father took Mike to see a psychiatrist.

After examining Mike, the doctor said that if Earley was lucky, his son was using illegal drugs because the alternative was that he had a mental illness.

“I was shocked by his words,“ Earley said. “But today I understand them perfectly. At that time, I knew nothing about mental illnesses and how they can be cruel.”

First Arrest

After the episode at McDonald’s, Mike went to see a psychiatrist twice. But stopped going because he did not believe he was ill, only that he needed to eat better foods.

For a while, he seemed well and the family decided it was a fluke. For nine months everything was fine and then one day Mike had a serious break. He became sick and broke into a house when there was no one at home. He went into the bathroom and took a bubble bath. The homeowners decided to press criminal charges again him even though he was sick.

He was charged by the police with a serious crime. The prosecution could mark him forever as a criminal and would have serious repercussions. Fortunately, a female police officer helped his son and he was found guilty of a lesser crime.

A year later, the police officer was murdered by a 18 year old man with mental problems.

Care

People tell Earley not to help his son. They said he must let his son hit rock bottom, then Mike will figure out that he must take medicine. Only if he hits rock bottom will Mike finally understand that you must follow the treatment on a regular basis.

These people do not realize that letting an ill person hit rock bottom could mean that the person will end up committing suicide, Earley said. Studies show a high percent of persons with bipolar disorder try to kill themselves. The patient really believes that he can be fine without medication – that is another characteristic of the disease.

People say that a person with mental illness has the right to be crazy and be homeless on the street and psychotic. But these people do not feel that way about someone who has Downes Syndrome. The parents of a child with Downes Syndrome are never criticized for advocating for their children. Children with Downes Syndrome are not allowed to be homeless on the streets. But both Downes Syndrome and bipolar disorder are brain disorders.

“My son has a disease. A disease that affects your brain and steals your capacity to make decisions.”

Suffering the Greatest

The worst thing for a father or a mother is to be unable to solve their children’s medical problems. “As parents, we are responsible for loving and protecting our children. But when one of them has a mental disorder, our love is not enough. I feel anger. I feel frustration, and I cry because Mike is sick. It is horrible to look at the face of my son and realize that in times of psychosis, it is as if I were not his father.”

Punishment and Treatment

In the US, a patient can not be treated against his will unless he becomes dangerous and poses a risk to himself or someone else.

“In this way, the law punishes my son rather than helps him because the American health system will not respond until my son becomes dangerous. Of course, when he becomes dangerous, the criminal justice system steps in and arrests him. People need to understand a basic fact about mental illnesses: they rob people of the ability to make smart decisions. What is frustrating is that we know how to help many of these patients. About 70% of them benefit from the medication available. But with the current laws, instead of giving them tools to lead a reasonably normal life, we abandon them on the street where they are accused of being lazy, addicts, drunks and bums. Blame is preferred to helping them.”

Ideal Health System

In the United States, nobody can be involuntarily confined for more than 72 hours without having the right to appear before a judge with a lawyer, with the exception of the perpetrators of very serious crimes such as murder. At that hearing, a judge decides whether the person should be taken to a hospital against their will.

The U.S. courts have ruled that unless a person is immediately dangerous, they can not be forced to get help. For example, a man with schizophrenia who eats his own excrement can not be detained in a hospital because eating feces is not an act dangerous — that is what a judge ruled.

“From my point of view, a better way would be for the court to appoint three psychiatrists to examine patients and give an opinion about whether or not they require hospitalization. My son believes that the ex-President George W. Bush was behind the September 11 attacks in New York. That is his political opinion and he has a right to believe that. But when he says he can fly or that I am not his father, it is clear that his mind is deceiving him and his illness is deceiving him and he needs help. How can I not help him?”

The Future

Mike was doing well when the book published in 2006. But since then has had two serious crises. Both occurred after he stopped taking his medication.

“At one time, he was afraid that I would call the police so he drove to North Carolina (270 km away). He called and said voices were telling him that he would die if he left the car.”

Mike refused to tell where he was but he agreed to drive home and with the help of others, we got him to take his medicine. I want what every parent wants for his son: a good job, a family and happiness. But it is difficult for Mike. He is currently without work and is not married. My priority is to help him stay well. Mike is lucky because he has brothers and sisters who love him and who will help him if he gets sick after his mother and I are no longer here.

How to Tackle Homelessness and Mental Illness

“The Soloist” Enlightens: A Compassionate, Useful Message on How to Tackle Homelessness and Mental Illness

This article by Pete Earley was originally published in USA TODAY

As the father of a son with a mental illness, I cringe whenever Hollywood releases a movie with a main character who has schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. All too often, the ill person is depicted as a psychotic killer or an odd-ball genius whose disorder is enlightening rather than debilitating. The Soloist avoids these clichés and gives audiences a realistic look at how untreated mental illnesses can ravage the lives of its victims. Based on a true story, the film portrays the friendship that develops between Los Angeles Times columnist Steve Lopez and Nathaniel Ayers, a homeless, gifted musician with schizophrenia.

The frustration that Lopez feels is all too familiar to families such as mine, as he attempts to help Ayers navigate a mental health system that a national presidential commission appointed by

George W. Bush found to be “fragmented and in disarray.” But the reason I cheered when The Soloist ended was not because of the problems that it documents, but rather two solutions that its screenwriters subtlety introduced into the script.

The first step Lopez takes to help Ayers is to get him into the Lamp Community, which moves him into an apartment. Lamp is not a fictional creation. It is one of the most successful housing programs in the nation. It practices what is called “Housing First,” a concept that puts homeless persons into apartments immediately without requiring sobriety or participation in medical treatment. This is completely opposite of traditional housing programs that refuse to rent apartments to persons who are not mentally stable or sober.

Importance of Housing

Housing First advocates argue that it’s impractical to expect a homeless person struggling with a chronic mental illness, or a drug or alcohol addiction, to focus on recovery if he is sleeping under bridges and being attacked by thrill-seekers. Before someone can recover, he needs a safe place to live. Lamp and other Housing First practitioners emphasize that they listen to what their clients want, rather than demanding they behave a certain way.

But clients are not simply handed an apartment key. Tenants pay 30% of their income for rent (if they earn nothing, they pay nothing) and in most cases, they must meet with a team from the Assertive Community Treatment Association twice a month. Rather than demanding that an ill person report to a dozen agencies for help, ACTA sends a team of professionals directly to clients in their apartments.

A team usually includes a psychiatrist, social worker, nurse, substance abuse counselor, vocational rehabilitation worker and peer specialist (a person who has a mental illness but is managing it successfully).

High Success Rate

Lamp’s personalized approach claims an 85% success rate, which is the highest in the nation and extraordinary considering that many of its clients lived on the streets for decades.

The Corporation for Supportive Housing, a national group that provides funding for groups such as Lamp, insists that supportive housing not only helps people recover but also saves tax dollars by reducing costly emergency room visits, stays in state mental hospitals and nursing homes, and the use of jails and prisons as de facto asylums.

Linda Kaufman, who runs Pathways to Housing, a successful housing-first group in Washington D.C., says such programs could end chronic homelessness for people with serious mental illnesses in the nation’s capital within five years if units were available. It is not a question of knowing what to do, she explains, but a question of whether we will do it.

The other solution The Soloist offers comes at the movie’s end, when Lopez notes that while he was unable to heal Ayers’ mental illness, he did become his friend. While Lopez modestly questions the importance of his friendship, the late Tom Mullen, who created a much-honored recovery program in

Miami for severely mentally ill convicted felons, called friendship paramount to recovery: “These are the most isolated persons in our society. How can someone become mentally well if they are viewed as social lepers?”

Perhaps that’s the most valuable lesson here. Once Lopez saw Ayers as a person, it was more difficult to hurry by him on the street. The psychotic, homeless man pushing a grocery cart suddenly wore a human face.